United States

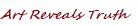

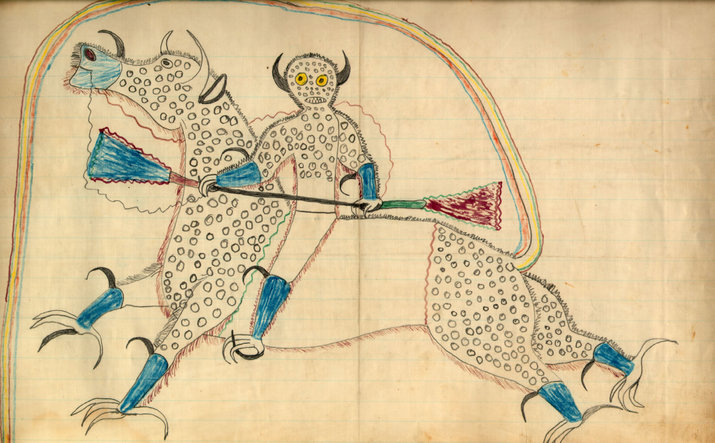

A Kiowa Ledger Drawing

The picture above belongs to a class of narrative illustrations known as "Ledger Drawings". These were created by Native Americans who lived on the Plains of the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Driven from ancestral homelands and onto reservations, the Native Americans recorded events on pieces of paper taken from ledger books of reservation managers. The illustrations augmented story telling, the vehicle which transmitted oral tradition from generation to generation. Ironically, many Ledger Drawings were created while the Native Americans were imprisoned at Fort Marion, in St. Augustine, Florida.

It is believed this picture (above) represents an 1874 battle that took place between the Kiowa and the United States Army, at Buffalo Wallow in the Red River War.

Why do we appreciate art? Why do we create it? Does art have extrinsic value, besides the price it can fetch at auction?

Why do we appreciate art? Why do we create it? Does art have extrinsic value, besides the price it can fetch at auction?

These are not easy questions, and each of us will likely have a different answer. One thing is certain, though: governments throughout history have recognized the power of art, and have sought to control artistic expression. This is so, because art speaks. Often, it speaks for those who have been denied a voice in the public forum.

These are not easy questions, and each of us will likely have a different answer. One thing is certain, though: governments throughout history have recognized the power of art, and have sought to control artistic expression. This is so, because art speaks. Often, it speaks for those who have been denied a voice in the public forum.

Almost all the art shown on this page represents the experience of people under occupation by a foreign entity.

Almost all the art shown on this page represents the experience of people under occupation by a foreign entity.

Art may speak with the force of a spear. This is evident in some of the pictures displayed here.

Art may speak with the force of a spear. This is evident in some of the pictures displayed here.

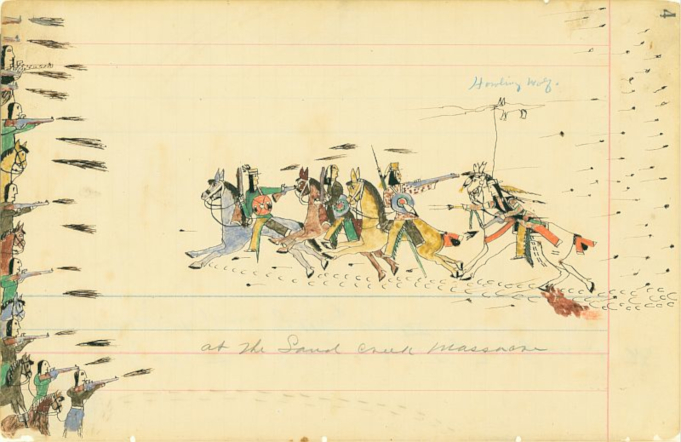

Ledger Art by Cheyenne Chief Howling Wolf

This drawing depicts a massacre of Native Americans that took place at Sand Creek, New Mexico in 1864. According to scholars at the Smithsonian, "Sand Creek was the My Lai of its day, a war crime exposed by soldiers and condemned by the U.S. government". The massacre was remarkable for its brutality, which included mutilations and the slaughter of women and children. It was also remarkable for the great number of witnesses left behind, who testified to what had occurred. One of the witnesses, Chief Howling Wolf, drew the picture displayed above.

Sometimes art speaks obliquely. In certain cases, oblique messages have a more enduring influence than those delivered sharply.

Sometimes art speaks obliquely. In certain cases, oblique messages have a more enduring influence than those delivered sharply.

Ledger Drawing by Lakota Sioux Chief Black Hawk

%20public.jpg)

This picture features a heyókȟa, "one of the most powerful medicine people of the Lakota" tribe. The heyókȟa is an important figure in Lakota culture. He/she is part of the tribal mythology that connects the past to the present. Many of the remedies that have been traditionally favored by heyókȟa are used today.

Peru

Pictures of graphic violence are in this section. If these will disturb you, please stop reading now.

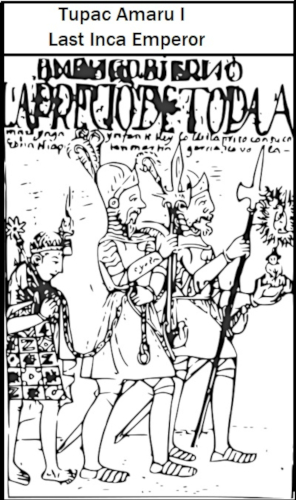

Imprisonment of Tupac Amaru I

This illustration shows Tupac Amaru I, last Inca Emperor, as prisoner of Spanish soldiers. Before his capture, Tupac had led the remnants of the Inca Empire in rebellion against the Spanish. The picture here was drawn by Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala (1535-1616) in his book, "Nueva Crónica y Buen Gobierno".

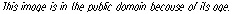

The Execution of Tupac Amaru I

Tupac Amaru I had only been emperor for a short time when he was captured. During his imprisonment, he was subject to intense religious instruction and underwent conversion to Christianity. Once the conversion had taken place, he was decapitated. His head was placed on a spike. The head became an object of veneration (the Inca believed their emperors were immortal and worshiped their mummified remains.), and attracted great crowds.

The Spanish removed Tupac Amaru's head from the spike and buried it.

The Execution of Tupac Amaru II

It is said that the man who called himself Tupac Amaru II was a descendant of Tupac Amaru I. As his namesake had done before him, Tupac Amaru II led a rebellion against the Spanish. And, as had transpired with his predecessor, Tupac Amaru II was captured and executed. However, his execution was even more brutal than had been that of his antecedent.

He was sentenced to have his tongue cut out. He was forced to watch the torture and murder of his family. He was also sentenced to have his body torn apart by four horses running in different directions, but this didn't work. So the Spanish untied him from the horses and decapitated him. After Tupac Amaru's death, his body was cut into pieces. These pieces were distributed to different parts of Peru.

The gruesome deaths of Tupac I and Tupac II were meant to dampen the spirit of rebellion, but had the opposite effect. For generations, even to the present, the name Tupac Amaru has been an inspiration for rebellion. The pictures drawn by Guamán Poma de Ayala helped to keep their stories alive.

Vietnam

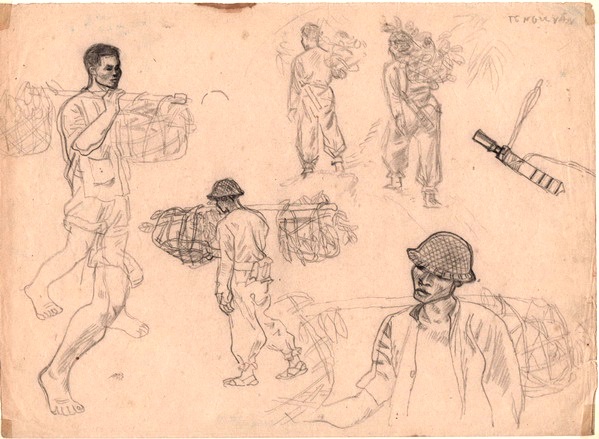

Evacuation, by Tô Ngọc Vân (1908-1954)

The author of this picture, Tô Ngọc Vân, (1908-1954) was said to have quoted Picasso: “War can be waged through painting.” This was perhaps a way of saying that art speaks powerfully.

Tô Ngọc Vân began his career as a painter under French colonial rule. His early work showed a strong European influence and consisted mostly of idealized landscapes and portraits. After the Viet Minh's August Revolution, Tô Ngọc Vân's work changed. He created posters, and pictures such as the one above, which carried strong political messages.

Australia

Aboriginal Hollow Log Tombs

Image credit GFDL v1.2 license: Flagstaffotos

This installation of hollow log coffins is on display at the National Gallery of Australia, in Canberra. The artists who designed the coffins are members of clans whose traditional homes are in Central Arnhem Land, Australia. The Hollow Log Coffin installation represents "all the indigenous people who, since 1788, have lost their lives defending their land". The artists wanted their work to be displayed publicly, so future generations would remember, and honor, the struggles of their people.

indian bird icon2 group Krewinkel-Terto de Amorim public.jpg (https://cdn.steemitimages.com/DQmT4TarDeDPMNPT6tbx8FvCfoWoiNn5pNLHiFocYg2aom5/indian%20bird%20icon2%20group%20Krewinkel-Terto%20de%20Amorim%20public.jpg) indian bird icon2 group Krewinkel-Terto de Amorim public.jpg (https://cdn.steemitimages.com/DQmT4TarDeDPMNPT6tbx8FvCfoWoiNn5pNLHiFocYg2aom5/indian%20bird%20icon2%20group%20Krewinkel-Terto%20de%20Amorim%20public.jpg)

Brazil

Art Preserves culture.jpg (https://cdn.steemitimages.com/DQmTSbzcng1cjtHFUJLb25vuiBG44cKumduKLSrAP8Pr85X/Art%20Preserves%20culture.jpg)

The Prophet Daniel, by Aleijadinho

Profeta Daniel3 Pgaraujo Aleijadinho 4.0.jpg (https://cdn.steemitimages.com/DQmbR16krru5EFP5spo6igNp82ZbQWCh1RbHyzenJYnKbTV/Profeta%20Daniel3%20Pgaraujo%20Aleijadinho%204.0.jpg)

Photo credit: Pgaraujo. Used under CC 4.0 license.

The statue pictured above is one of twelve sculptures created by Antonio Francisco Lisboa at the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus of Matosinhos, in Brazil. Antonio Francisco Lisboa was more popularly known as Aleijadinho (the lame one) because, it is said, he had leprosy.

Aleijadinho's twelve towering statues depict the twelve apostles. While many critics believe these sculptures are posed as ballet dancers, one scholar, Monica Jayne Bowen, from Brigham University, sees more culturally relevant elements. She sees in the graceful poses an emulation of capoeira, a style of fighting with Afro-Brazilian origins. Ms. Bowen explains that the relative positions of the apostles and their gestures are typical of capoeira combatants. She asserts that the statues are "political propaganda" and " a call for liberation". While it was likely not safe for Aleijadinhoto to make such a statement openly, under Portuguese occupation, it would be relatively safe for him to send a subtle message through art.

indian bird icon2 group Krewinkel-Terto de Amorim public.jpg (https://cdn.steemitimages.com/DQmT4TarDeDPMNPT6tbx8FvCfoWoiNn5pNLHiFocYg2aom5/indian%20bird%20icon2%20group%20Krewinkel-Terto%20de%20Amorim%20public.jpg) indian bird icon2 group Krewinkel-Terto de Amorim public.jpg (https://cdn.steemitimages.com/DQmT4TarDeDPMNPT6tbx8FvCfoWoiNn5pNLHiFocYg2aom5/indian%20bird%20icon2%20group%20Krewinkel-Terto%20de%20Amorim%20public.jpg)

art disc wave gif.gif (https://cdn.steemitimages.com/DQmeRb4DXLjKcUWAzAAw3z9UwDVyxDBnC75TrsUntfvbYjz/art%20disc%20wave%20gif.gif)

india flower2 group.jpg (https://cdn.steemitimages.com/DQmW6FM1RntykSe4TyQsiDS3UJQaMtSbxsQQ3qepC8uwqG7/india%20flower2%20group.jpg) india flower2 group.jpg (https://cdn.steemitimages.com/DQmW6FM1RntykSe4TyQsiDS3UJQaMtSbxsQQ3qepC8uwqG7/india%20flower2%20group.jpg)

India

Art Protects Legacy.jpg (https://cdn.steemitimages.com/DQmPrS23AaeCQVyjhk69cCrCcFLVJM8YEXRHxGYE48GGDJ4/Art%20Protects%20Legacy.jpg)

Bharat Mata, by Abanindranath Tagore

Bharat Mata3 bengal school.jpg (https://cdn.steemitimages.com/DQmVDREC4pQ72o9U5NQwMgXeb1udustWu9RWU1oMZAZQwZC/Bharat%20Mata3%20bengal%20school.jpg)

public domain.jpg (https://cdn.steemitimages.com/DQmfB3ucEfnysd9nVGSBMPuu85qiS3xw2yqr5znQHddDoe3/public%20domain.jpg)

British colonial rule began in India with the Battle of Plassey in 1757. British domination of India lasted for almost two hundred years. Such a long period of colonial rule had a profound effect on Indian culture, and specifically on Indian art. In order to survive and prosper in this environment, many Indian artists (according to the Discover Society,) "... tried to adjust their painting styles to suit British preferences".

*However, the