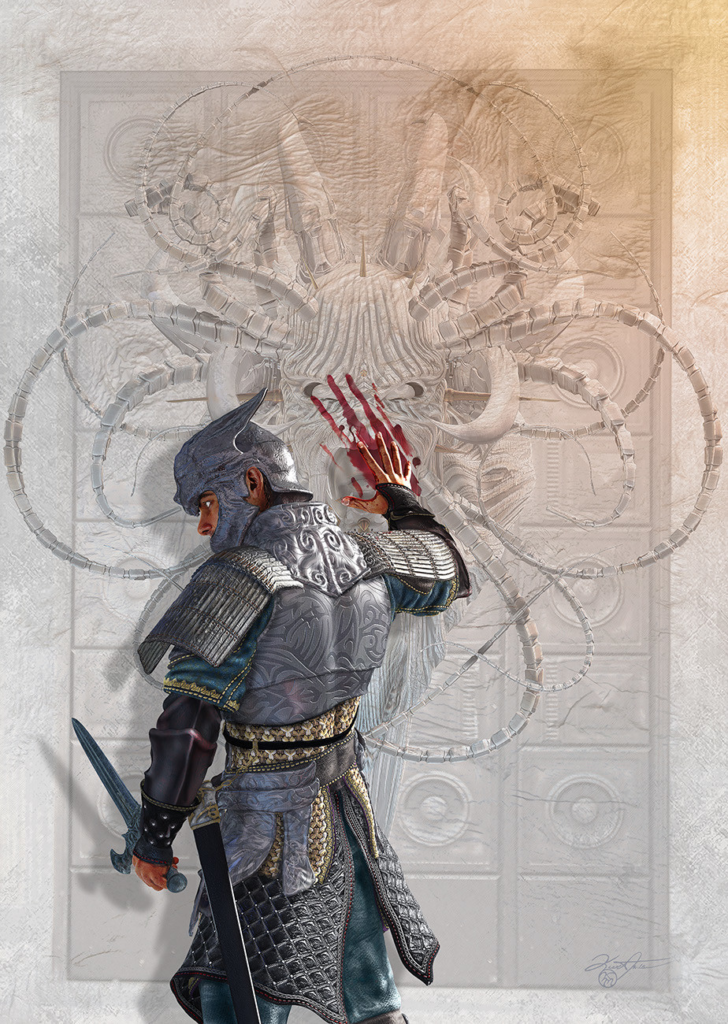

(Credit: Kurt Miller)

I don’t like Larry Correia’s Saga of the Forgotten Warrior.

I realise this is an unpopular opinion to hold. This has nothing to do with the author’s politics. It has nothing to do with his personality either. And it is only tangentially related to him picking social media fights with everyone in my circles whenever he publishes a new book. My reaction to his series is based on a more fundamental reason:

It is forgettable.

What Could Have been

Saga of the Forgotten Warrior is not a bad series. If anything, it should be great.

Here’s how it is described:

--

After the War of the Gods, the demons were cast out and fell to the world. Mankind was nearly eradicated by the seemingly unstoppable beasts, until the gods sent the great hero, Ramrowan, to save them. He united the tribes, gave them magic, and drove the demons into the sea. Ever since the land has belonged to man and the oceans have remained an uncrossable hell, leaving the continent of Lok isolated. It was prophesized that someday the demons would return, and only the descendants of Ramrowan would be able to defeat them. They became the first kings, and all men served those who were their only hope for survival.

As centuries passed the descendants of the great hero grew in number and power. They became tyrannical and cruel, and their religion nothing but an excuse for greed. Gods and demons became myth and legend, and the people no longer believed. The castes created to serve the Sons of Ramrowan rose up and destroyed their rulers. All religion was banned and replaced by a code of unflinching law. The surviving royalty and their priests were made casteless, condemned to live as untouchables, and the Age of Law began.

Ashok Vadal has been chosen by a powerful ancient weapon to be its bearer. He is a Protector, the elite militant order of roving law enforcers. No one is more merciless in rooting out those who secretly practice the old ways. Everything is black or white, good or evil, until he discovers his entire life is a fraud. Ashok isn’t who he thinks he is, and when he finds himself on the wrong side of the law, the consequences lead to rebellion, war—and destruction.

--

Epic scope, vast sweep of time and space, grand politics, a remorseless killer armed with a legendary weapon. It’s everything epic fantasy is supposed to be.

The characters have human motivations and vulnerabilities. The plot is serviceable. The prose is workmanlike. The action scenes approach expectations.

And for all that… it is as forgettable as the titular Forgotten Warrior.

Nothing about the series particularly stands out. I have to rack my brains to think of something particularly memorable. I don’t have this problem with other books by other masters of the craft. Even stories derided as ‘isekai trash’ are more memorable than this. And Larry Correia is supposedly one of the best fantasy writers of my generation.

Why?

If I have to put my finger on it, it’s this:

Larry Correia doesn’t do anything with the culture the story is supposedly inspired by.

Indian Names, American Hearts

Saga of the Forgotten Warrior is described as Indian-inspired fantasy. These days, the term ‘X-inspired’ means that it has the superficial trappings of an exotic culture painted over a fundamentally Western story.

Saga of the Forgotten Warrior is no different.

If you replace the name of every character in the series with familiar Western names like Alice and Bob, you’ll notice something very strange: Every single character thinks, talks and acts like an American.

Indian English is influenced by British English and Indian languages. To sell the setting, everyone should at least at least retain traces of Indian English. Yet every character speaks in idiomatic American English.

I realise, of course, it can be very difficult for a non-Indian to correctly use Indian English. I myself have criticized many a foreigner for incorrectly using Singlish and Mandarin. Yet there are simple ways to integrate Indian English into this setting without running the risk of making significant mistakes.

Indians use the Indian numbering system when referring to large numbers, saying ‘lakh’ to mean a hundred thousand and ‘crore’ for ten million. Interjections like ‘aiyo’, ‘aiye’, and ‘na’ are easy to insert without breaking up dialogue. And Wikipedia has a list of Indian English vocabulary that can be inserted into speech and writings.

Little touches like these can sell the setting without creating an overly-alienating linguistic environment or risking significant errors. Yet we don’t see this in this supposedly Indian-inspired setting.

It is also not difficult to incorporate Indian social customs. For example, haggling is a major aspect of Indian culture. There are no fixed prices until all sides come to an agreement. Everything is up for negotiation, be it salaries, dowries, service fees, even individual vegetables sold at the market.

The implication here is everyone should be negotiating with everyone else over everything.

One character in the series is a merchant. Explicitly showing this merchant haggling with other vendors would reinforce both the setting and the character. Especially if he is shown to be much better at haggling than everyone else.

Likewise, the politicians and leaders in this setting have to be skilled at striking bargains and negotiating with others. Especially leaders of groups with little to no hard power at their disposal, or leaders who need to bring together many disparate groups.

Going beyond language and customs, there is nothing about the characters that strike me as particularly Indian. Again, if you replace their names with ‘Alice’ and ‘Bob’ and the like, you’ll find that every main character is Western—even American—at heart.

Indian culture is hierarchical, yet communal. There is high power distance and top-down decision making, but the wise leader usually attains consensus among his subordinates before formally committing to a decision. Communication is indirect to avoid giving offense, especially to one’s superiors. Etiquette is important, personal relationships paramount. Tradition is valued, and so is caution. Punctuality, however, is a suggestion, and people liberally interpret deadlines and meeting times.

Indian culture places family ties in high regard. Family is obliged to support family. In a caste society, this goes one step further: those of the same caste are expected to help other caste members, and enforce social norms within and between castes. The actions of one person reflect not only on the individual, but also on the extended family, and the entire caste.

There would be plenty of opportunities for drama. Major characters wrestling with their consciences, trying to decide whether doing the right thing is worth the inevitable backlash against them, their families, and their caste. Characters across the caste strata taking advantage of family ties—and casting out those who don’t obey this norm. Characters upholding the caste system out of fear that rebellion will bring even worse consequences. Rebels struggling to create and adapt to the norms of an egalitarian society, and occasionally falling back to the old ways. Characters taking certain actions to raise their status or the status of their community, even if it comes at great cost, especially if it doesn’t make sense.

And yet, in Saga of the Forgotten Warrior, every major character is individualistic. Few of them consider the impact of their decisions on others, be it their families, subordinates, or fellow caste members. Those who do inevitably make decisions based on personal considerations, only paying lip service to second- and third-order effects on their communities. Save for the politicians, speech is usually direct, even blunt. Every major character has a high risk appetite compared to his peers. Rebels have little to no trouble adjusting to a world without castes, even—especially—those used to the privileges of higher castes.

Every single character comes off as American—not Indian.

It’s not wrong for one or two characters to display such traits. That makes them stand out in such a setting. This also gives American readers an audience surrogate, someone through whom they can understand the setting. But when everyone acts American, then it is not Indian fantasy. Other than the arranged marriages and the faux-caste system, there isn’t much Indian culture in this setting.

In Book 3, a politician takes time out to explain the intricacies of his political machinations to another character. He is trying to indirectly build consensus among those he is influencing. Yet to an Indian—to someone raised in a communal environment, with communal-based politics and consensus-driven decision making—none of this would need to be explained. It would be obvious.

There is a perfectly good way to justify this explanation. The character receiving the explanation is a librarian. She spent her life around books, not people. It would be quite natural for her not to immediately grasp the social implications of the intrigue unfolding around her, and to need someone to explain what is really going on.

But, and this is the critical part: in such a setting, this is a disability. Or otherwise highly unusual. How can a person with poor social skills survive in an environment that demands highly-attuned social skills? A real-world analogue would be an autistic person who has never received formal social skills training bumbling his way through society.

The politician wishes to recruit the librarian as an advisor. But since she is already socially disadvantaged in the great game of politics, how does this make sense? It’s one thing for him to occasionally consult her on her areas of expertise, quite another to expect her to participate in high-stakes decisions. Here we can see how cultural norms directly influence character interactions and the plot, and why there must be alignment between them.

At the same time, the implications of the politicians’ actions might not be obvious to an American reader. One raised in an individualistic society might not understand the need for consensus building. He might not even realise what’s going on. So Correia has to spell things out to an American reader.

There are two naturalistic ways to do this. The first is to have the librarian think about the situation, and then come to the appropriate conclusions. She is slow on the uptake, because socialising doesn’t come naturally to her, but not totally ignorant. The second is for the politician—and other characters—to treat her as slow, disabled, or otherwise like a developmentally-delayed child who needs what is obvious to them explicitly spelled out to her.

To be fair, I recall at least one incident in which the librarian does figure things out on her own. I only wish that this were the rule, and not the exception.

Series protagonist Ashok can also serve as an audience surrogate. A character like him does not and cannot understand the importance of social skills. (The reason for this is revealed in Book 1.) It would be quite natural for characters to explicitly explain social matters to him—and also to treat him as stupid or disabled. At least behind his back.

The story would be far more intriguing if everyone except Ashok and the librarian acts according to the norms of Indian culture. These characters are treated the way autistic people are treated in our world, with other characters having to explain social situations to them, or help them navigate such treacherous waters. This would go a long way towards selling the setting and satisfying the needs of readers from Western societies.

Especially since the caste system isn’t enough to hold up the setting.

Of Caste and Culture

The hallmark of Saga of the Forgotten Warrior is the caste system. The former priests and royalty became outcastes, and in their place, the judges and the lawmakers stand on top. This superficially makes sense… until you think about it.

In ancient societies, class and caste systems were designed to answer the following questions:

- How should society be organized?

- How should those of great skill and talent be recognized and supported?

- How should those of lesser skill and talent be allowed to contribute?

- What is the basis of rulership?

The Indian caste system has four castes. The brahmins are the clergy. The kshatriyas are the warriors, rulers, and administrators. The vaishyas are the artisans, merchants, tradesmen and farmers. The shudras are the labourers. And then there are the untouchables, who handle the dirty work.

The priests stand on top because they are the closest to the gods and are the most educated. The warriors, however, have the right to rule, because they hold the monopoly on violence. Power flows from the edge of a sword, and those who command the sword command the world.

Feudal Japanese society followed a similar logic. The samurai were both warriors and rulers. The daimyo were high-ranking samurai, and the shogun was himself a warrior, the general-in-chief of the armies of Japan. The Emperor and the Imperial Court were merely figureheads. In times of war, high-ranking samurai led armies of low-ranking samurai and conscripted peasants into battle. In times of peace, samurai enforced the law and administered their fiefs.

The samurai ruled because they wielded the sword. Anyone who opposed them would be cut down.

Japanese priests, having renounced the material world, were not part of the Japanese class system. Nonetheless, the wise shogun will pay his respects to even the humblest priest, because the priest represents the transcendent—and, more to the point, represents a source of soft power that even the shogun cannot deny.

Again, in Europe, we see a similar pattern of the ruler-warrior. The king is the sovereign, who commands the military forces of the nation. The nobility are lesser lords with armies at their command, who are bound to answer the king’s commands in times of war. The knights are professional warriors in the service of the ruling class.

During the early Middle Ages, the clergy was not formally considered part of the class system, but they still wielded immense influence over society. Later, when the Christian Church grew in wealth and power, the clergy were formally incorporated into the upper classes, such as the French First Estate_._

Why do we see this societal structure across different culture? Because war in ancient times demanded highly-skilled warriors. It took an average of ten years to train a samurai or a knight. Likewise, the weapons and armour of professional warriors represent significant investments of time, money, and resources.

During those ten years of training, with the exception of the poorest of warriors, young squires are not working the fields or otherwise performing other productive labour. After they are recognized as full-fledged warriors, they were either serving their liege or training for war. Again, other than the poorest warriors, they are not performing economically productive work. In addition, the time, money and resources expended in producing military equipment cannot be used to produce food or other economic goods.

Someone else has to perform the labour that keeps society running, and that burden falls on the lower classes.

The lower classes provide for the needs of the upper classes. The upper classes in turn protect, guide and rule the lower classes. This is the logic of class and caste systems everywhere in the world. And because the upper classes hold power—soft power for the priests, hard power for the warriors—they enforce the social order.

Now let’s look at the caste system of Saga of the Forgotten Warrior. The clergy and royalty were overthrown, but presumably, the educated class remained. The intelligentsia reorganized themselves as the legal caste and became the new rulers, with the right to pass laws and judge disputes, whereas the warrior caste reserved for themselves the right to bear arms and enforce the law.

The caste system of the setting reflects the idea of civilian control of the military. The civilian legal caste controls the warrior caste. But this doctrine derives from the early modern era. It comes from a milieu based on ideas such as government coming from the consent of the governed, that true political power flows from the will of reasonably equal citizens, and that the military exists to defend society and not to define it.

Such ideas cannot apply to the story. The society is profoundly unequal and hierarchical. The strong command and the weak obey. The common people have no voice. Civilian control of the military cannot possibly emerge in a setting where people are unequal and civilians have no say. Power defines society, not defends it.

Without the priests, there is no soft power. There is only hard power: the power of the Law, and the power of the sword that backs the Law.

What is to stop the warriors from taking over? Why did the warriors even surrender part of the right to rule to soft civilians?

To his credit, Correia does address these issues. Aside from the warriors, there are three independent paramilitary groups: the Inquisitors, the Protectors, and the House of Assassins. And there are also bandits in the setting. The lawmakers would deploy them against warriors whose ambitions exceed their grasp. And the series does, indeed, feature warriors aiming to overthrow the first caste—and the first caste realizing just how impotent they are without the support of the warriors.

But the question is: why did it take so long?

After the revolution that overthrew the priests, the warriors held all the power. Why would they surrender part of it to a new caste of secular priests? Why didn’t they choose to reign at the top? How could the judges prevent this?

In other words: what steps did this society take to create and maintain a modified Hindu caste society as opposed to a feudal European or Japanese society?

In the books I’ve read, these questions aren’t adequately answered.

At the very least, instead of an inseparable division between the warriors and the judges, the relationship between them would be symbiotic. The judges and the lawmakers give the warriors legitimacy, while the warriors defend the legal caste. The balance of power would be a constant dance of negotiation, with the judges holding the power to declare the warriors illegitimate (and thus targets for annihilation), and the warriors holding the power to wipe out the judges.

This would make for more interesting—and naturalistic—politics.

There are so many ways Correia could have made use of the Indian caste system—but didn’t. There are innumerable subcastes within each caste, which have varying degrees of prestige. Polygamy was permitted for rulers in ancient times. Most of the lower castes were restricted to certain jobs, but the brahmins could take on any job they pleased, even menial labour. The laws, norms and customs of a settlement were defined by its majority caste. Many settlements were inhabited solely by people of a certain caste. In multi-caste areas, caste councils mediated relationships between castes, with the leaders of each caste administering justice to members of their own castes as well as those of other castes who sought them out. Strict rules prevented the intermingling of castes, including intercaste marriage, so much so that if someone of a higher caste married someone of a lower caste, both were ostracized and their children relegated to a low-status subcaste.

There is so much richness available through this one conceit—yet Correia does little with it. And so, instead of a truly Indian setting, we simply get a generic fantasy setting with Indian tra