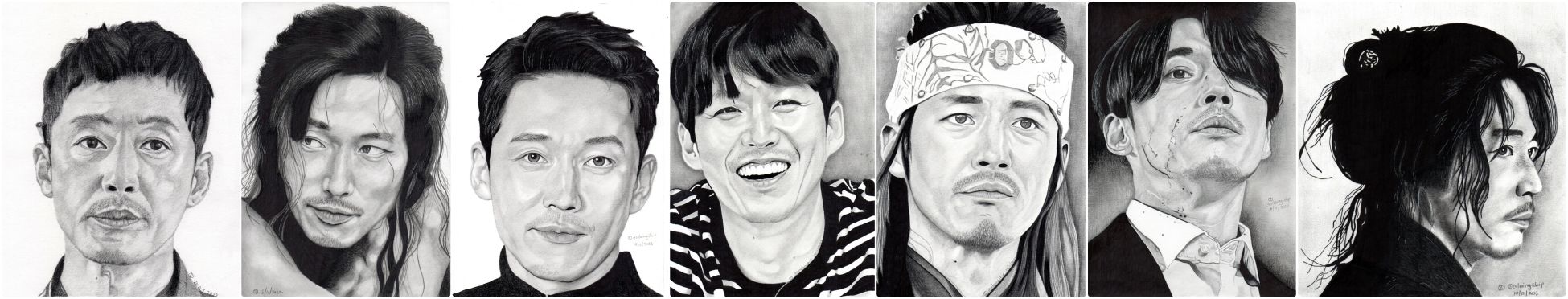

When I first read the prompt, “What skill would you like to learn?” I hesitated. My mind didn’t wander to something new, like playing an instrument or taking up pottery. Instead, it returned to what has recently taken up the most of my heart and time: immersing myself in my people’s stories. I’ve been documenting my family history, translating Iban folktales into English and Malay, and researching the animistic beliefs that influenced how my ancestors lived in the past. It may not seem like a skill in the traditional sense, but it needs patience, dedication, and a consistent commitment to learning.

This kind of learning doesn’t feel like adding something new to my life; it feels more like uncovering something that was always there. I now realize that remembering is a skill in and of itself. It requires listening, interpreting, and writing in a way that stays true to the original voice while still making sense in today’s language. It is a craft that requires me to sit with pieces—sometimes just a phrase, a half-remembered childhood folktale, or a story told from one elder to another—and give them structure without losing their meaning.

In the past couple of years, I’ve been interested in customs, dreams, and oral traditions that were once a big part of the Iban’s daily life. Our ancestors believed that dreams weren’t just random things our brains conjured but guidance or warnings from the spirit world. To learn about these beliefs is to learn how closely they were tied to nature, animals, rivers, and things we can’t see. It’s not easy to translate stories like this. Each word has layers, and when you put them in a different language, each layer can change the meaning. I’m learning how to translate not just words but also worlds.

This process has shown me that preservation is an active skill. You can’t just admire a culture from afar or talk about heritage in general terms. To preserve heritage, you have to write it down, understand it, and pass it on. I know that these stories could disappear at any time if no one bothers to pass them on. It feels like weaving: taking loose strands and tying them together to make something strong enough to last.

I think often of my children. I picture them reading these writings one day and seeing parts of themselves reflected back. They might read about how brave their ancestors were or the rituals that used to guide community life. This could make them feel both wonder and a sense of belonging. That hope keeps me going. I don’t want them to get just bits and pieces. I want them to have a living archive that they can go back to when they feel rootless or want to know more about themselves. In this way, writing is both a gift and an inheritance.

This learning also helps me understand my own role in the chain. I’m not just preserving stories for the future; I’m also standing in the middle, receiving them from the past. There is humility in this position. Sometimes the stories seem too big for me to tell or too sacred to put into words. Sometimes I feel like I’m not qualified, like I’m trespassing on something I don’t fully understand. I feel like an imposter. But then I remember that this is also part of the task. Even if you’re not sure, simply paying attention is a form of dedication.

There are also challenges. To translate, you need to do research, compare things carefully, and sometimes spend a long time staring at a confusing sentence. Writing family histories requires being careful and accurate when deciding which details to include and which to leave out, as well as how to honor different voices in the same story. It’s not glamorous to learn these skills, but they make me more patient and give me more respect for those who came before me.

I’ve also been thinking about how I write. As someone who doesn’t speak English as their first language, I’ve had a hard time developing a consistent style. I wonder if my words will ever sound as smooth or polished as those of people who grew up with the language. But the more I write, the more I see that my culture and heritage are not barriers but strengths. They give me a writing voice that is shaped by the rhythms of the Iban language or by the oral storytelling traditions. These are the things that set my writing apart from a lot of other people who write about the same things. I could only come into my own when I embraced who I truly am: an Iban woman rich with cultural memory and life experience.

I’m also thankful for the resources that make this work possible. Old books, articles, and museum archives have been lifesavers for me because they have helped me learn things I couldn’t have found on my own. There are many people who worked hard and spent time writing down and putting together our culture into words. I wouldn’t be able to keep writing if they didn’t do their part. This gratitude keeps me focused and reminds me that I am part of a much bigger effort to keep culture alive.

If I had to sum up what I’m learning, I’d say that three things stand out. First, the ability to really listen to what is said and what isn’t said. Second, the ability to translate not only between languages but also between different meanings. Third, the skill of preserving, which means having the courage to hold memory in your hands and carefully write about it for the future generations. And now, maybe a fourth: the ability to trust my own writing voice, even when it sounds different than the ones expected.

So when I answer the prompt, “What skill would you like to learn?” my answer isn’t easy to show. I want to keep learning how to remember things. I want to get better at writing authentically, listening closely, honoring my culture, and sharing what I can while I am still here. These skills may not make a lot of impact, but they are important. They might not get a lot of praise, but they could keep a culture alive.

That's it for now. If you read this far, thank you. I appreciate it so much! I'm a non-native English speaker, and English is my third language. Post ideas and content are originally mine. Kindly give me a follow if you like my content. I mostly write about making art, writing, poetry, book/movie review and life reflections.

Note: If you decide to run my content on an AI detector, remember that no detectors are 100% reliable, no matter what their accuracy scores claim. And know that AI detectors are biased against non-native English writers.

Note: All images used belong to me unless stated otherwise.