My first name, Olivia, was given to me by my aunt, who was an avid Olivia Newton-John fan. She loved the music and for her, the name represented something beautiful and worth passing on. So I became Olivia, named after a beautiful and talented singer.

Growing up, I didn’t think much about it. It was just my name, four syllables, easy enough to pronounce, and slightly more trendy than the names around me. But back then it was common to see kids with names such as Donny Osmond or Cliff Richard. It was tacky, I admit, but I still take the compliment of being named after a superstar. However, over time, I began to notice how names carry stories and I realized mine was only half told.

While Olivia came from pop culture, my second name came from something far older, deeper, and more spiritual. It was given to me in honor of a woman in my family, a great-grand-aunt who was once an early 20th-century Iban master weaver of the sacred pua kumbu (ceremonial cloth). She was not only skilled in her craft but also legendary. In our culture, women like her were known as “indu takar, indu ngar.” These were women who could receive weaving patterns in dreams from the supreme deity, Kumang, and translate them into woven cloths imbued with spiritual power.

In days of old, the pua kumbu held a sacred role in the ritual and festival of enchaboh arung, where severed enemy heads were received. These clothes were woven by the wives or mothers of Iban warriors, guided by spiritual forces from the heavenly realms of Panggau Libau and Gelong. Upon their husbands’ and sons’ return from war, the women would spread the pua kumbu across their arms, welcoming them home and placing the enemy heads upon the cloth. (Refer to the footnote for more details).

For Iban women, including my great-grand-aunt, weaving was more than just a craft. It was their “warpath,” parallel in sacredness and risk to the men’s headhunting expeditions. Before they could begin a new ceremonial piece, they needed to receive it in a dream and enter a specific spiritual state. One wrong move, even in how they prepared their threads, may lead to misfortune or even death. Their work carried great responsibility and risk. It required focus, discipline, and faith in the divine.

I may not entirely understand the weight my great-grand-aunt bore, but I have always felt an echo of it. Receiving her name was an inheritance. It connected me not only to her but also to the spirit of her work and her path.

I don’t weave cloth, but I do write and draw. Often it begins with a dreamy vision, like a found phrase or an emotion that I can’t fully articulate. There’s always that strong urge to make sense of it and mold it into something tangible. When I started my artist website I wanted it to be a personal and meaningful space. As Virginia Woolf once said, this is a room of my own. This is a space where I could shape something substantial based on my truths.

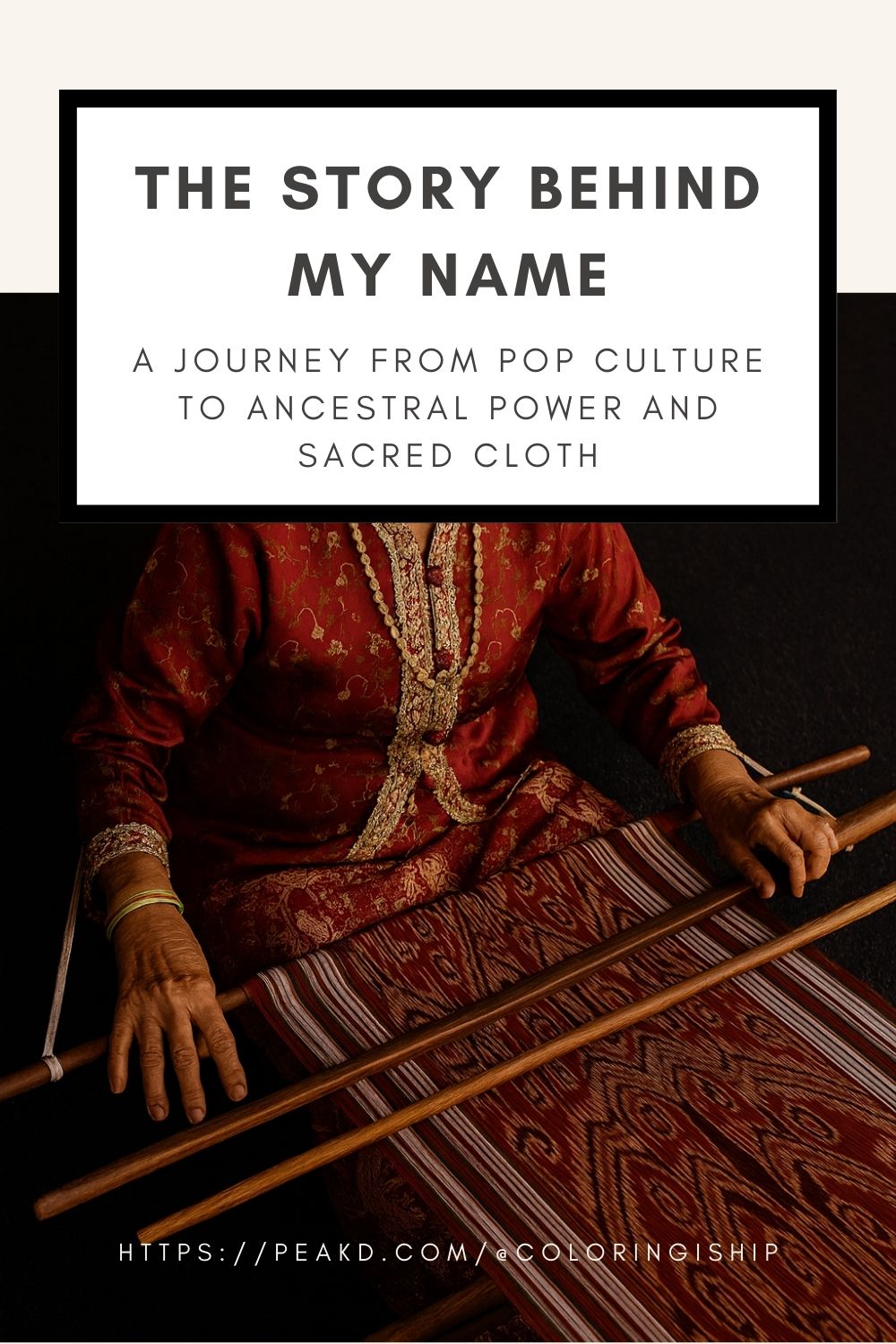

Recently, I updated the website header to reflect more of where I come from. I didn’t want anything generic or trendy but I wanted something that expressed my culture and heritage. So I chose an image of pua kumbu, the sacred textile woven by women like my great-grand-aunt. It carries more than visual beauty, with rich deep reds, blacks, and intricate patterns throughout. It holds power, dignity, and sacredness.

To some, it may just look decorative. However, for me, it serves as a subtle way to assert my identity and heritage in this fast-moving, globalized world.

My great-grand-aunt likely never imagined her name and legacy would live on in a digital space, passed down to a woman who lives a century apart. But I think of her often when I work, especially late at night when the house is quiet and I am writing or drawing. I wonder if this page I write or draw on is my version of the loom.

That thought changes the way I approach my work. I don’t follow trends or write for algorithms. I build my work and portfolio slowly and with care. I try to create things that have meaning, even if they are simple. This is my way of remembering and continuing a legacy that is otherwise pushed aside by the more flashy things the crowd chases.

I won’t mention my great-grand-aunt’s or my second name here. Some things should be kept private but rest assured, I carry her with me. She is part of my story and also why this blog exists.

I was named after a singer whose voice brought joy to many. And I was also named after a woman whose hands transformed dreams into sacred cloth. Both of those women live inside me. They influenced how I perceive the world and the way I write or create.

When you visit my website and notice the patterned header, know that it holds a layer of memory and pride of a culture. It holds a legacy and strength that runs beneath everything I share.

I have a first and a second name. One name was given; the other inherited, and both live on in everything I write and create.

Footnote: After returning from war expeditions, Iban warriors would spend about a week in huts away from the longhouse, cleansing themselves and preparing their “war trophies” (enemy heads). The heads were carefully skinned, the brains removed, and then smoked for several days. Once properly preserved, the warriors dressed in their finest regalia for a grand arrival during the enchaboh arung festival, where the skulls were placed into the waiting arms of their wives or mothers.

That's it for now. If you read this far, thank you. I appreciate it so much! I'm a non-native English speaker, and English is my third language. Post ideas and content are originally mine. Kindly give me a follow if you like my content. I mostly write about making art, writing, poetry, book/movie review and life reflections.

Note: If you decide to run my content on an AI detector, remember that no detectors are 100% reliable, no matter what their accuracy scores claim. And know that AI detectors are biased against non-native English writers.

Note: All images used belong to me unless stated otherwise.