Hello everyone!

I’m bringing you a heartbreaking story about Jazovka. There will be mentions of brutality and killing so please if you aren’t comfortable with that, skip this post.

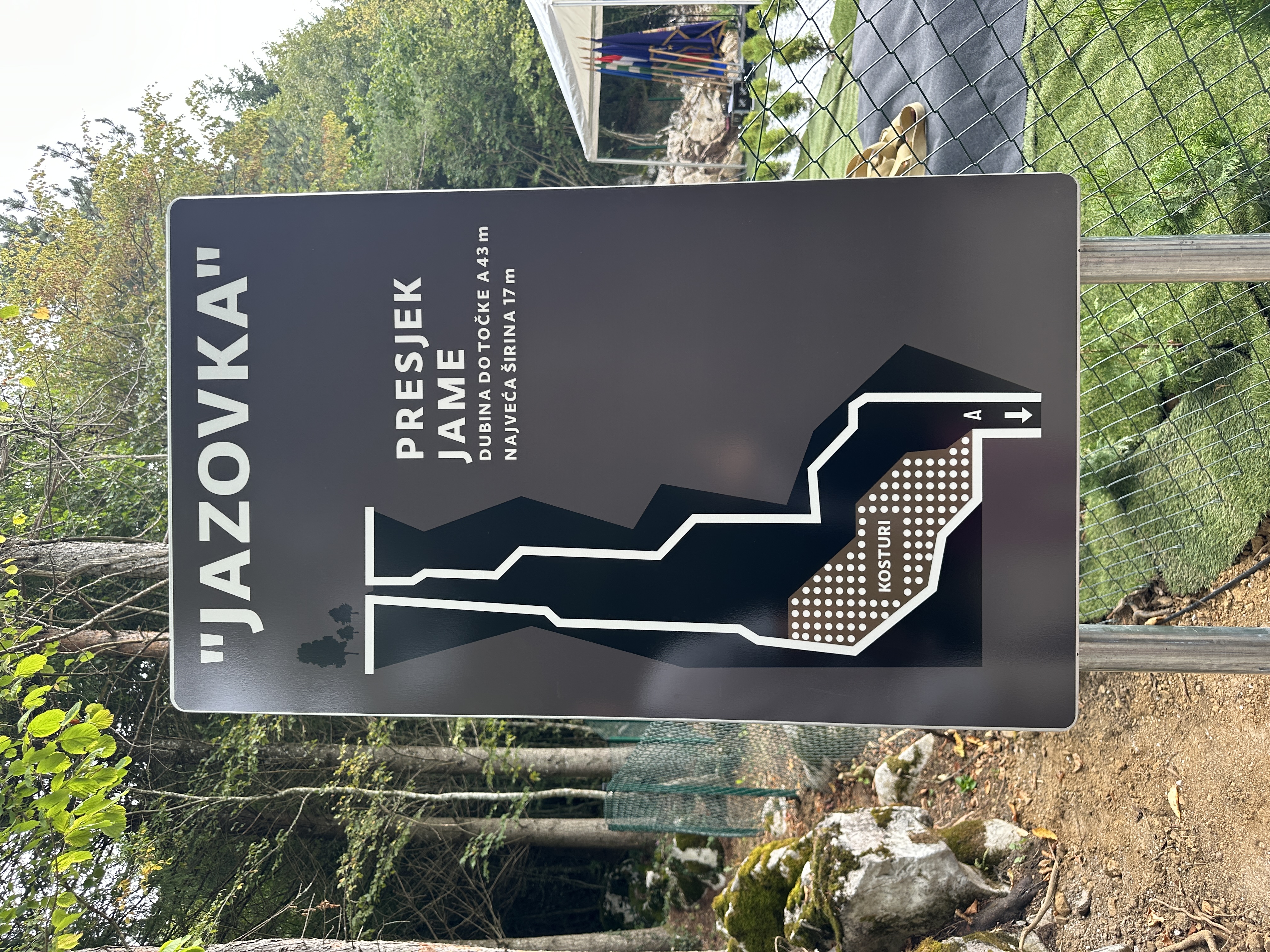

High in the Žumberak mountains, hidden by dense forests and narrow paths, lies a place that became one of the darkest symbols of war and post war killings in Croatia. The Pit Jazovka.

For decades, this pit was only a whisper among families, a wound carried in silence, and a place where hundreds of innocent people were thrown to their deaths and their young lives taken away.

Among them was my great grandfather.

He was not a criminal, he was not a killer, and he certainly did not deserve such an end. He was betrayed and killed by his first neighbor; someone who should have stood as part of the community. But he tore a family apart and left a wife without a husband and a child without a father.

And yet, his story was only one of hundreds. We are lucky to know that he was among those innocent souls that ended here. There is one more pit just like this, that still hides mass bodies, mass crimes and a genocide of Croatian people.

What Happened at Jazovka?

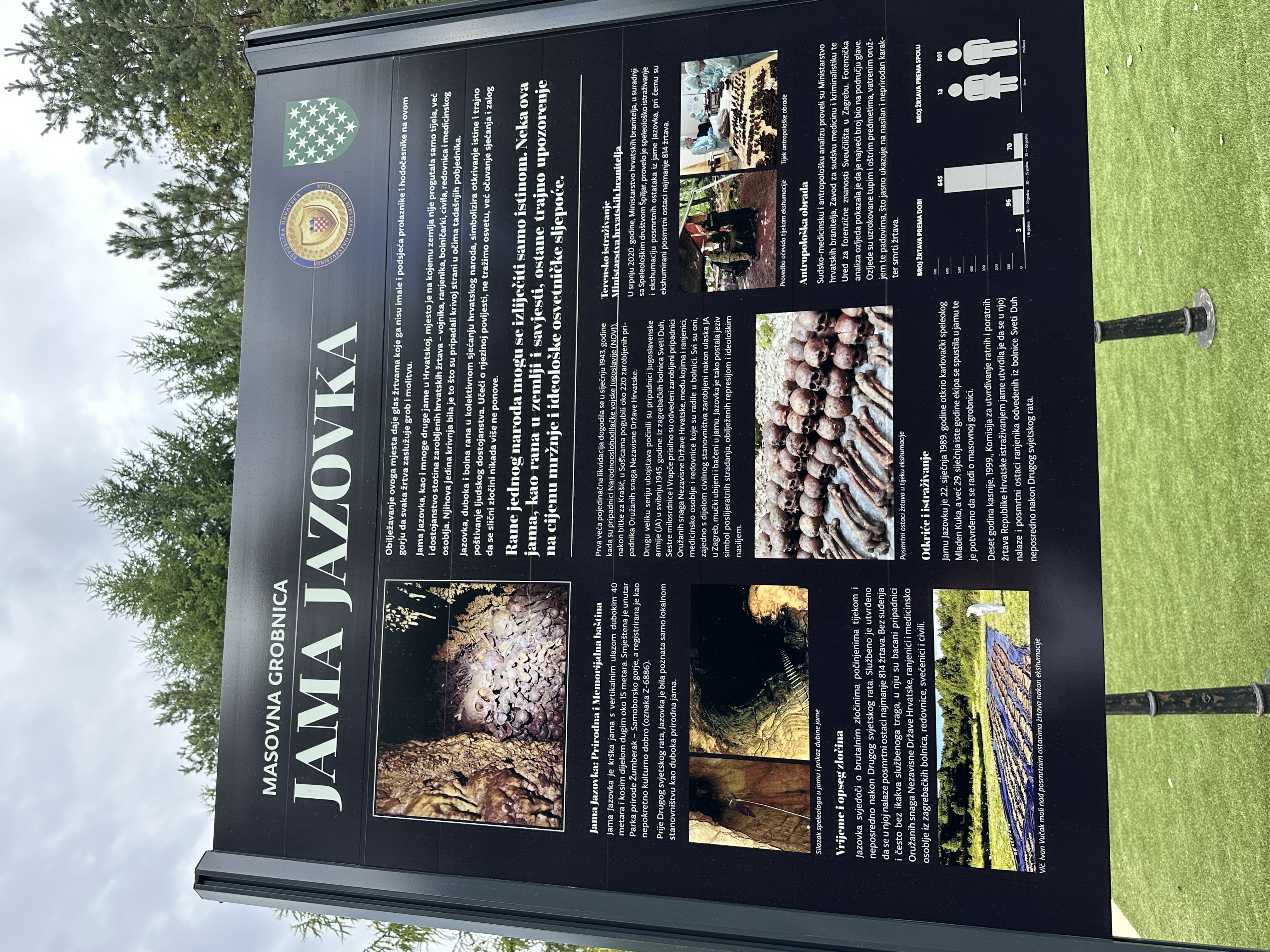

During and after World War II, Partisan forces carried out mass genocide of innocent people that had nothing to do with the war, wounded soldiers, medical staff, civilians, and prisoners from Zagreb hospitals and prisons. Instead of trials or justice, they were loaded into trucks and driven into the woods above Sošice. There, their arms were tied with wire in pairs or groups or their bodies were simply thrown in into the darkness in hopes that they will be forgotten.

The cruelest part was the method. Survivors testified that the first in the line was often shot or left wounded after they stabbed him in the throat with the knife, and as he fell into the pit, he would drag the others with him. Death came not only from bullets but from the fall itself, from suffocation in the dark, or simply from being buried alive under the weight of other bodies.

One survivor, Mijo Samac, later gave a chilling testimony. I will put the whole testimony that he gave to Dr. Juraj Batelja's book "Victims Shrouded in Silence - Testimonies of Sufferers from the Stations of the Cross". I would also recommend “Pakao se zove Jazovka” - “Hell’s name is Jazovka” by the person that found Jazovka Mladen Kuka.

“Mijo Samac was born on September 23, 1920 in Slavetić, a settlement below the Žumberak Mountains. His parents were Franjo and Mara née Bravar. Called up as a conscript into the Croatian Home Guard, he went to Karlovac on March 15, 1942 to serve his military service. In peacetime, military service lasted two years. Mijo was called up during the war, so the duration of his military service was indefinite.

Until December 1942, his battalion was mainly stationed in Karlovac and did not go outside the city on any war operations. However, before Christmas 1942, his company had to go to a war position on Žumberak. They headed towards Krašić. There was already a military garrison in Krašić guarding the place, mostly elderly men. Among them were Home Guard, reservists, gunners, and mobilized people as Ustaše (thirtieth battalion). There were about 300 of them. They felt threatened, because there were several thousand partisans in Žumberak. Mijo's company was assigned to them as an aid.

Mijo described the attack on Krašić in January 1943. They were attacked by the 13th Proletarian and 4th Korduna Brigades of partisans, about 3,000 of them. Krašić was a hindrance to them because they did not have free movement from Žumberak to the railway and the Banovina.

The defenders resisted all night and the second day, despite the cold, snow and lack of ammunition. The fighting was terrible, and the partisans intended to completely liquidate them. Part of the defense fell in positions around the cemetery, the church of St. John and the chapel of the Holy Family. Commander Šega with two ensigns and two senior sergeants decided not to surrender and activated the bombs, dying on the spot.

The remaining 12 or 13 of Mijo's comrades surrendered to the partisans who surrounded them and ordered them to lay down their weapons. Mijo described the dramatic hours and days full of crime as follows:

"We were just soldiers, regular Croatian soldiers, not mercenaries, criminals or enemies of the people. The partisans, mostly of Serbian nationality from Kordun, decided to take them to Sošice, where they would be judged by a 'people's court'.

We were well dressed. We had raincoats and good shoes on. Not for long. Soon the order followed - to take off our raincoats and some of our clothes. One of our men asked them how we were going to continue without clothes and shoes? One partisan replied: 'You don't need anything anymore. You are going to a pit. You will be comfortable there. You will not be cold or hot.'

I had never heard of that pit before, nor had anyone ever spoken of it to me. We were exhausted and exhausted. We didn't sleep for two nights. We held out because we were young. In our prime, from 20 to 22. They tied us together with thick wire, two by two. We still had our shoes on. It was Sunday. The people were going to celebrate mass. Our enemies forced us to come near the church. They shouted that we were bandits, Pavelić's gang, etc. They thought they would hold some kind of people's court there. And the people sympathized with us, cried and ran away. No one paid attention to their calls to come and mock us, spit on us, show contempt and rebuke us.

They led us two by two, tied with wire. All of them, soldiers and civilians, who they accused of supporting the connection with us, from Krašić and other surrounding villages. They lined us up, tied two by two, in a column. They ordered the column to move through Hruškovac, Prekrižje, Begova brdo, Oštrec to Sošice. We arrived in Sošice late at night. They divided us into two parts: one part of us was placed in the basement of a burned monastery, and the other part in a ruined, burned school.

_**We were there for one day. Individual partisan provocateurs came to us, insulted us and cynically asked us if we knew where we were going and what awaited us. We just kept quiet. They told us that we were all sentenced to death because we resisted the partisans in Krašić and that all of us, without distinction, whether we were Ustashas,

Home Guardsmen or civilians, would all be terribly punished. At that, one of our warrant officers, who was wounded, said that we were not attacking them, but that they were attacking us, and we were only defending Krašić. As soon as he said that, his fate was already sealed. They trampled him in front of us and then killed him.**_

The next day, they drove us to the fairground, before the people's court. We were exhausted and starving. In the meantime, they brought people from Radatovići and other supposedly partisan villages and prepared them to shout the words of the verdict at us like an incited mob: Kill! Kill. They shot at us as soon as they arrived or dug out from under the snow: wood, stones, etc.

First, Milka Kufrin, originally from Okići, took the stage. Her husband Rade Bulat, Lutvo Ahmetović and others also went up.

The 'people's court' first called out Lieutenant Ivan M. from Duga Resa. He was not even 30 years old. Probably one of the members of the court harbored hostility towards him. They killed him in front of us, saying beforehand that he would be replaced and that his people would come for him. What a deception! As he fell to the ground, shot, he spread his arms with his last strength and shouted: ‘Long live Croatia!’. I heard later that his people came for him and took him in a coffin.

Then Marko Belinić climbed onto the stage, which was actually an old car. He read us the verdict, which read: ‘In the name of the people of Žumberak, you are sentenced to death! All of you without distinction. You have no right to pardon and the verdict is to be carried out today!’

By then there were just over 300 of us. After the verdict was read, he proudly walked off the stage, and a terrible silence fell among us. We all simply froze. A young man named Jure, from a village in Žumberak, was tied to me, and he said to me: ‘Mija, it’s all over now. Even dear God himself can’t help us anymore!’ I replied: ‘All that’s left for us is to pray to God!’

The snow was knee-deep, the temperature was around -17 °C. We had to take off our shoes and clothes. We looked at each other in mystery, so I asked the soldier tied next to me: ‘So what kind of pit is this, where will all of us, over 300 of us, be able to be accommodated?’ Hearing my question, the partisan guard who was watching us maliciously exclaimed: ‘We have room for all of you and even more of you!’

I felt increasingly tired. Luckily, I had thick winter socks on my feet that my late sister Bara had made for me. But more than the cold, I was tormented by uncertainty. Soon, one of their commanders approached us, with their heavy security and knives on their rifles. I thought that the pit was somewhere far up there, in Sveta Gera, or that it was some kind of bend that Sošica would throw us into not far away.

I also thought that perhaps one of their units was already stationed up there, killing us as we came. He gave the order for the column to move towards Jazovka. A strong guard escort was moving with us and behind us. It was truly a journey into the unknown. Above the village was a sparse forest. We walked barefoot on thick, frozen snowdrifts. Our eyes had not yet noticed anything, and our bodies were moving frozen towards a small hill. When we reached the designated place, at the opening of the Jazovka pit-abyss, they stopped the column.

The fog began to lift and we all watched the horrors of the inhuman treatment of us. God gave me the grace that I was not among the first in the column, but at the very end, in the very last row. One of the partisan soldiers, the executioners, issued an order or announcement in a raised and important voice: ‘Now the liquidation will begin and you can watch how it is done! As it will be with the first, so it will be with the last. Not one of them will escape!’

That almost happened. We were not the only ones trembling with fear. I also saw trembling and uneasiness in some of their guards who were watching over us. It was a gruesome act. At about half past one, the slaughter and mass killing began.

‘They slaughtered with knives’

Those in the front rows of the column were the first to be slaughtered. Our enemies did not want to waste ammunition, and they also wanted to avoid the sound of gunfire in the settlement, so they slaughtered our people ten by ten with knives and threw them into the pit. Our soldiers had to approach or were forcibly brought in two by two, tied up, separated into dozens, and each one was stabbed in the neck. One of the butcher's partisans would pull the victim forward by the hair, and the other would plunge a knife into the back of her head. Some were killed with a bayonet.

They were not dead immediately, but they were writhing and struggling in the snow. All the snow was bloody. I was very scared and kept praying to God to help me. The butchers had several people with them who collected the killed and half-dead and threw them into the pit, while they slaughtered ten others. It was terrible to hear how, when they threw them into the pit and noticed that there was still a victim alive, they would say to each other: 'Let him writhe inside, there will be enough room!'

Soon night began to fall. There were 20 to 30 of us left alive. Then suddenly, from the direction of Sošice, their courier appeared, riding a horse. He brought some kind of message on a piece of paper. When he came close to the pit, he shouted: ‘Stop! Stop! Enough! What has been killed, has been killed!’

While he was shouting, the executioners decided to slaughter four more couples and said that they could slaughter as many as they wanted. When they stopped, there were about 12 of us left, six couples. My companion, who was tied up with me, told me that they would now hang us from an oak tree as a decoration and a mockery. Fortunately, that did not happen. Those of us who had remained after the slaughter were taken back to the village, tied up, and locked in a former inn: ‘Kod Radića’. We were locked up there all night.

_**The guards in front of the gate were guarded by hostile guards until morning. We wondered what they were waiting for? And for how long? We heard the guards’ words and huddled in a corner. They were the two butchers I had seen at the pit. They had red scarves around their necks, with the mark of a hammer and sickle. They had freshly bloody knives around their belts, and the blood of our men had soaked their clothes and splattered their hands. One of them shouted at us: ‘Come on, you Ustashas,

tell me, which one of you is an Ustashas!’ We said that there were none and that we had joined the army by invitation. They did not touch us.**_

Within a day or two, they assigned us to work in their hospital, to care for their wounded, because we were better trained than them. When they had recorded our personal information, they told us this: ‘If ever, anywhere, in a hundred years you tell what happened, you will go up there again and die there for eight days.’

They took the four prisoners to an unknown location, and they entrusted me and three others with the care of the wounded Slovenians and other soldiers who had been brought in. We worked under the strict supervision of one of their men armed with an automatic rifle. They were afraid that we would do anything against any of the wounded, either outside the house, or try to escape. They threatened us that if we tried to escape, they would take us back and throw us in Jazovka. And I did not feel like running away.

The psychological state and mental anguish I was experiencing were crushing me and I certainly would not have done anything reckless without an extreme reason and despair. In these circumstances, I endured from Three Kings to Candlemas (February 2, 1943). It was hard work, and time passed slowly. Mistrust and silence reigned; I dared not ask anyone anything, I could not express my anxiety to anyone, I had to withdraw into myself.

I did not meet anyone I knew, nor did I hear a word from my birthplace. My family thought I had already been killed, thrown into a pit. The partisans created such terror among the population that none of my family dared to come to Sošice and ask about my fate.”

⸻

Silence, Denial, and Discovery

For years, Jazovka was hidden under silence. Speaking about it was forbidden, dangerous even. Families whispered about where their loved ones might have ended up, but no one dared to search openly.

It wasn’t until 1989, shortly before the fall of communism, that speleolog Mladen Kuka and his colleagues descended into the pit. What they found confirmed the stories: human remains, shoes, clothing, wire bindings, undeniable evidence of the crimes.

For the first time, the truth was no longer a rumor. The silence was broken.

⸻

Exhumation of the Victims

Decades later, Croatia began the painstaking process of recovering and honoring the victims. In 2020, an exhumation was carried out by experts from the Croatian Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs. 814 sets of remains were carefully retrieved from the darkness of Jazovka. Before that Mladen Kuka and the priest Ivan Vučak went to the bottom of the pit and held a mass for the innocent, then bones.

The numbers tell their own story of tragedy:

• 801 men

• 13 women

• 3 children younger than 16

• 96 young people aged 16–20

• 645 adults between 20–35

• 70 adults between 35–50

The remains were small, often just fragments, but also bones and skulls packed into little caskets. No DNA analysis was done (which I’m devastated in but it’s also very expensive and hard to do after so many years) they were identified only as male or female, child or adult.

In Sošice, 2025, on a Saturday the Black Ribbon Day, officially known in the European Union as the European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Communism and Nazism and also referred to as the Day of Remembrance for the victims of all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes victims were given a proper burial.

Families, like mine, could only stand and wonder: Which one of these holds the remains of our loved ones?

Priests, veterans, and families gathered in silence, with tears, prayers, and candles. After so many years, the victims of Jazovka finally felt the sun on their bones, only to return to the ground but this time with dignity, with honor, and with remembrance.

⸻

My Family’s Wound

I grew up visiting Jazovka with my family. Every trip was haunting. Standing at the edge of the pit, I imagined what those people endured. The fear, the darkness, the hopelessness. It was never just a hole in the ground; it was a graveyard without markers, a place where so many lives ended.

I don’t carry hate in my heart. I don’t hate the Partisans, and I don’t glorify the Ustaše. My family history simply is what it is. With a bowed head, I honor every innocent life lost on all sides. Each of people killed in the war was someone’s child, parent, sibling. Each deserves a candle and a prayer.

⸻

History, Faith, and the Warning of Stepinac

Archbishop Alojzije Stepinac once said:

“Communism is born of lies, lives on lies, and will die in lies.”

For him, communism was not just a political system but an attack on truth, faith, and human dignity. Jazovka stands as a reminder of