Hoy quiero compartir con ustedes una experiencia profundamente reveladora que viví en mi aula de tercer grado, una que no solo reforzó mi fe en el poder de la estrategia pedagógica, sino que también me recordó la responsabilidad que tenemos de ir más allá del currículo para sembrar conciencia crítica en nuestros estudiantes.

El tema era, la conmemoración del 12 de octubre, conocido en nuestro país como el Día de la Resistencia Indígena. Un contenido del área de Ciencias Sociales cargado de historia, dolor, resistencia y la compleja redefinición de nuestra identidad. Sin embargo, me encontré con un muro inesperado: el olvido.

Iniciamos la clase con un conversatorio, confiada en que, al menos, recordarían los elementos básicos. La pregunta: ¿Alguien recuerda qué celebramos cada 12 de octubre fue respondida con un coro de silencios y miradas vacías? No había rastro de Cristóbal Colón, de las carabelas, ni de la lucha de los pueblos originarios. Sus mentes, curiosas y llenas de vida, habían archivado esa fecha como un simple día festivo, sin mayor significado.

La anécdota que definió el momento fue tan graciosa como aleccionadora. Al preguntarles si recordaban los coloridos penachos que solíamos elaborar con plumas y material de provecho, una de mis niñas, con esa sinceridad que solo un niño puede tener, exclamó:

¡Maestra! No recordamos nada de qué se celebra… ¿Será el día de la gallina? Porque eso lo hacemos con plumas de gallinas

La risa fue inevitable, pero la reflexión, profunda. Detrás de esa inocente confusión, había un mensaje claro; nuestras tradiciones escolares, aunque bien intencionadas (como los penachos y las dramatizaciones), se habían convertido en un fin en sí mismas. El símbolo (la pluma) había perdido completamente su conexión con el significado (la resistencia, la cultura). El "Día de la Gallina" era el síntoma de un aprendizaje desconectado, superficial y fácil de olvidar.

Ahí supe que no podía seguir con la planificación habitual del penacho. Tenía una cambiar ese concepto y construir, un aprendizaje significativo. Ya tenía preparada mi estrategia, y este fue el momento preciso para implementarla.

La Estrategia Implementada: De la Confusión a la Fascinación

Mi objetivo iba más allá de que memorizaran una fecha. Quería que sintieran el peso de la historia, que se maravillaran con la riqueza de nuestras raíces y que comprendieran por qué hablamos de Resistencia.

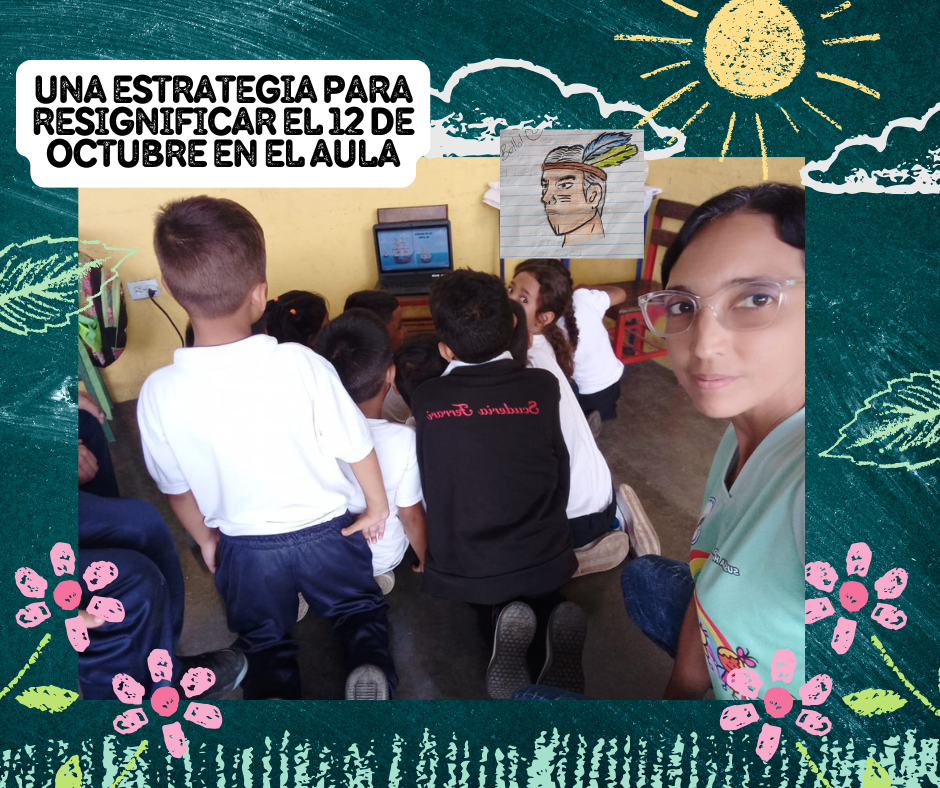

Sabía que un discurso monótono no lograría nada. En lugar de eso, destinamos 40 minutos a observar videos alusivos al tema. Aunque no contamos con video beam o proyector, eso no fue un obstáculo. Llevé mi laptop al salón, y para ellos, ese simple acto ya era algo novedoso y emocionante.

Visualizamos videos cortos pero poderosos:

-

Uno que explicaba, de forma adaptada a su edad, el encuentro entre dos mundos, enfatizando la perspectiva de los pueblos originarios: su forma de vida, su conexión con la tierra y el impacto de la llegada de los europeos.

-

Otro que mostraba la belleza y diversidad de las culturas indígenas venezolanas actuales, para que no las vieran como algo del pasado, sino como una parte viva y presente de nuestra nación.

Sus caras de fascinación lo decían todo. La pantalla pequeña se convirtió en una ventana a un mundo que desconocían.

La Conexión Emocional y Mítica de un aprendizaje: El Hermoso Autana

Aprovechando el momento de atención máxima, di un paso más. Introduje la mitología. Les conté la leyena de nuestro hermoso tepuy Autana, el Árbol de la Vida. Les hablé de cómo, para los pueblos indígenas Piaroa, este no es solo una montaña, sino el tronco sagrado de un árbol que una vez dio frutos para toda la humanidad, y cuyas cuevas son los restos de sus ramas caídas.

La magia operó. La historia dejó de ser algo lejano y ajeno para convertirse en un cuento maravilloso sobre su tierra. El Autana ya no sería solo una imagen en un libro; ahora tenía un alma, una historia. Este recurso narrativo fue fundamental para generar empatía y asombro hacia la cosmovisión indígena.

Consolidación del aprendizaje: El Dibujo como Reflejo

Finalmente, llegó el momento de la creación. Les pedí que realizaran un dibujo acerca de todo lo que habían visto y sentido. No les di instrucciones específicas. Quería ver qué había calado más hondo.

Obtuve un buen resultado, Ya no había manualidades de penachos genéricos. Ahora había dibujos de barcos llegando a costas desconocidas, representaciones del árbol de la vida con sus frutos luminosos, indígenas junto al Autana, y escenas que intentaban capturar el concepto de "encuentro" y "resistencia". Sus dibujos eran la evidencia gráfica de que el aprendizaje había sido internalizado y reinterpretado a su manera.

Una Guía en este proceso:

Esta experiencia me dejó varias lecciones que quiero compartir: 1.Diagnostica Siempre: No asumas que los estudiantes recuerdan o comprenden lo fundamental. Un simple conversatorio inicial puede revelar las brechas de conocimiento y permitirte ajustar tu estrategia.

2.Ve Más Allá del Símbolo Vacío: Las manualidades son valiosas, pero deben ir precedidas y acompañadas de un significado profundo. De lo contrario, corremos el riesgo de celebrar un "Día de la Gallina"

3.La Tecnología es un Medio, No un Fin: No necesitas los recursos más avanzados. Una laptop, una tableta o incluso un celular pueden ser ventanas poderosas al conocimiento si se usan con una intención pedagógica clara.

4.Conecta con lo Local y lo Emocional: La historia no son solo fechas y nombres. Utilizar la mitología, las leyendas y los lugares emblemáticos de tu región crea un puente emocional que facilita la comprensión y la retención.

5.Permite la Expresión Personal: El dibujo, la escritura creativa o el debate son herramientas esenciales para que el estudiante procese la información y la haga suya.

Hoy, mis estudiantes no solo saben que el 12 de octubre conmemora la Resistencia Indígena. Ellos ahora tienen una historia que contar, una imagen en sus mentes y, lo más importante, una semilla de respeto y curiosidad por las raíces que forjaron a Venezuela.

Sigamos transformando nuestras aulas, un aprendizaje significativo a la vez.

Gracias por leerme hasta el final. Imágenes tomadas con mi Redmi 10A. Imagen de portada editada en canvas.

English Version

Today I want to share with you a deeply revealing experience I had in my third-grade classroom. One that not only reinforced my faith in the power of pedagogical strategy but also reminded me of our responsibility to go beyond the curriculum to cultivate critical awareness in our students.

The topic was the commemoration of October 12th, known in our country as the Day of Indigenous Resistance. This social studies course was steeped in history, pain, resistance, and the complex redefinition of our identity. However, I encountered an unexpected barrier: forgetfulness.

We began the class with a discussion, confident that they would at least remember the basics. The question: Does anyone remember what we celebrate every October 12th? was answered with a chorus of silence and blank stares. There was no trace of Christopher Columbus, of the caravels, or of the struggles of the indigenous peoples. Their curious and lively minds had filed away that date as a simple holiday, with no greater meaning.

The anecdote that defined the moment was as funny as it was instructive. When I asked them if they remembered the colorful plumes we used to make with feathers and scrap materials, one of my girls, with the sincerity only a child can possess, exclaimed:

Teacher! We don't remember anything about what it's celebrating... Could it be Chicken Day? Because we do that with chicken feathers

Laughter was inevitable, but reflection was profound. Behind that innocent confusion, there was a clear message: our school traditions, although well-intentioned (such as feathers and role-plays), had become an end in themselves. The symbol (the feather) had completely lost its connection to meaning (resistance, culture). "Chicken Day" was a symptom of disconnected, superficial, and forgettable learning.

That's when I knew I couldn't continue with the usual plume planning. I had to change that concept and build meaningful learning. I had my strategy ready, and this was the perfect moment to implement it.

The Implemented Strategy: From Confusion to Fascination

My goal went beyond getting them to memorize a date. I wanted them to feel the weight of history, to marvel at the richness of our roots, and to understand why we talk about Resistencia.

I knew a monotonous speech wouldn't achieve anything. Instead, we spent 40 minutes watching videos related to the topic. Although we didn't have a video beam or projector, that wasn't an obstacle. I brought my laptop into the classroom, and for them, that simple act was already something new and exciting.

We watched short but powerful videos:

-

One that explained, in a way appropriate to their age, the encounter between two worlds, emphasizing the perspective of indigenous peoples: their way of life, their connection to the land, and the impact of the arrival of Europeans.

-

Another that showed the beauty and diversity of current Venezuelan indigenous cultures, so that they would not see them as something of the past, but as a living and present part of our nation.

Their fascinated faces said it all. The small screen became a window to a world they weren't familiar with.

The Emotional and Mythical Connection of Learning: The Beautiful Autana

Taking advantage of the moment of maximum attention, I went a step further. I introduced mythology. I told them the legend of our beautiful Autana tepui, the Tree of Life. I told them how, for the Piaroa indigenous people, this is not just a mountain, but the sacred trunk of a tree that once bore fruit for all humanity, and whose caves are the remains of its fallen branches.

The magic happened. The story stopped being something distant and foreign and became a wonderful tale about their land. The Autana would no longer be just a picture in a book; now it had a soul, a story. This narrative device was fundamental in generating empathy and wonder for the indigenous worldview.

Consolidating Learning: Drawing as a Reflection

Finally, it was time to create. I asked them to draw a picture of everything they had seen and felt. I didn't give them specific instructions. I wanted to see what had resonated most deeply.

I got a good result. There were no longer generic plume crafts. Now there were drawings of ships reaching unknown shores, representations of the tree of life with its luminous fruits, indigenous people by the Autana, and scenes that attempted to capture the concepts of "encounter" and "resistance." Their drawings were graphic evidence that the learning had been internalized and reinterpreted in their own way.

A Guide in this Process:

This experience left me with several lessons that I want to share: 1. Always Diagnose: Don't assume students remember or understand the fundamentals. A simple initial discussion can reveal knowledge gaps and allow you to adjust your strategy.

-

Look Beyond the Empty Symbol: Crafts are valuable, but they must be preceded and accompanied by a deeper meaning. Otherwise, we run the risk of celebrating a "Chicken Day."

-

Technology is a Means, Not an End: You don't need the most advanced resources. A laptop, a tablet, or even a cell phone can be powerful windows to knowledge if used with a clear pedagogical intention.

-

Connect with Local and Emotional Insights: History isn't just about dates and names. Using the mythology, legends, and iconic places of your region creates an emotional bridge that facilitates understanding and retention.

-

Allows for Personal Expression: Drawing, creative writing, and debate are essential tools for students to process information and make it their own.

Today, my students not only know that October 12th commemorates the Indigenous Resistance. They now have a story to tell, an image in their minds, and, most importantly, a seed of respect and curiosity for the roots that forged Venezuela.

Let's continue transforming our classrooms, one meaningful learning experience at a time.

Thank you for reading until the end. Images taken with my Redmi 10A. Cover image edited on canvas.