Finnegans Wake ‒ A Prescriptive Guide

Kate Strong

HCE’s history always repeats itself in the following generation. Our guide to this phase of the Earwicker affair is Kate, the elderly maid-of-all-works in HCE’s tavern. This is the same garrulous old woman who led us through the Museyroom in the first chapter. Kate is the compiler of the midden heap behind HCE’s tavern, in which all the history of the Mullingar House lies buried, patiently awaiting the trowel of some latter-day archaeologist. The strata of this rubbish dump are the pages of a book in which the whole history of Finn’s Hotel will one day be read. Kate’s dump also stands for Dublin itself―dumplan, as it is called in this paragraph. It is also Ireland and the world:

The rubbage dump is Ireland. ―Campbell & Robinson 82 fn

When Joyce created the character of Kate he did not conjure her out of nothing. He drew her from the pages of history. His principal model was a 17th-century Dublin woman called Katherine Strong, a toll-collector and city scavenger, who was charged with keeping the streets of Dublin free―from shit, mostly:

In the year 1634, Sir James Carroll was appointed Mayor of the City of Dublin [for the fourth and final time] ... The Corporation had appointed a Woman Scavenger, Katherine Strong, a widow ... the Mayor and Corporation had made her a grant of the Tolls of the market ... she was told at the Tholsel that she was to employ six men, with six horses and carts, to collect the refuse and sweep the streets very thoroughly, load the waste matter on the carts, and remove it to well outside the city―in fact beyond Oxmanstown Green [in the vicinity of the modern Stoneybatter]. ―Fraser 143

Strong did not take her duties very seriously. She dismissed four of her six employees with their horses and carts. She and her two remaining assistants proceeded to enrich themselves at the city’s expense. She abused her position of authority by extorting exorbitant tolls from the city’s labourers. She even had a brass “hat” made for herself, which she would fill with her tithe of local produce―fruit, vegetables, grain, etc. The streets, meanwhile, remained foul and offensive (Fraser 143). Any dung or refuse that she and her associates did pick up was promptly dumped into the River Liffey, which at one time became clogged. When she remarried, her second husband, a merchant called Thomas White, must have expected her to retire from the business, but her position was much too lucrative to consider taking any such action.

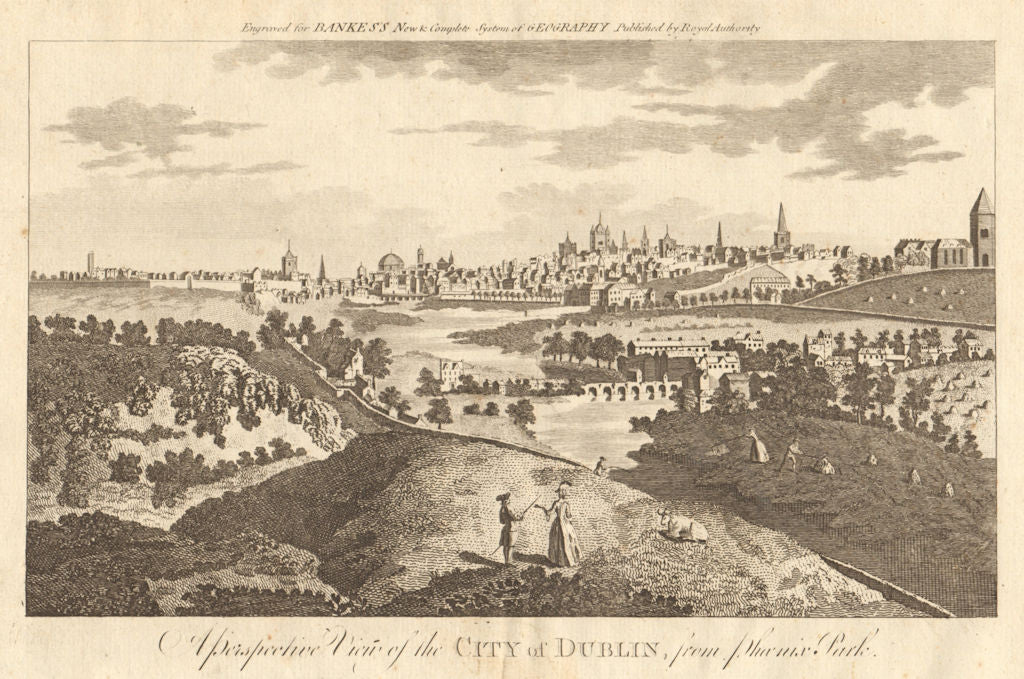

17th-Century Dublin Seen from the Phoenix Park

Sir James Carroll said of her that she cleans but sparingly and very seldom (McHugh 079.35), a phrase that Joyce echoes in this paragraph:

She is so much affected to profit as she will never find sufficient carriage to take away the dung, for where six carts are few enough to take away the dung of the city every week to keep it clean, she did and will maintain but two, which can scarce keep the way from the castle to the church clean, or that from the Mayor’s house to the church, neglecting all the rest of the city, which she cleans but sparingly and very seldom ... The foulness of the streets has been and still is so offensive to the state, and to all manner of people, and to the citizens also, as the city hath used all their power and means either to reform her or avoid her grant, but could never yet prevail against her, for they have caused many indictments to be found against her in the king’s bench, where they yet remain, and a great number more in the Tholsel, which were removed into the king’s bench by certiorari, and there lie dormant. And in that and all other courses that they have taken against her, they have been so crossed by her working as they could work no good against her; so as the more that she was followed the worse she grew, and kept the streets the fouler. ―John T Gilbert (editor), Calendar of Ancient Records of Dublin, Volume III, Page xxiii–xxiv

First-Draft Version

The first draft of this paragraph comprised only five or six lines of text and was written in November 1923:

Kate Strong, a widow, did all the scavenging in good King Charles’ days but she cleaned sparingly and her statement was that, there being no footpaths at the time[,] she left a filth dump near the dogpond in the park on which boot & fingerprints were of a very involved description. ―Hayman 75

The Dog Pond is the name by which Dubliners know the Citadel Pond in the Phoenix Park, which is all that remains of the moat of the unfinished Star Fort, or Citadel. Katherine Strong was charged with maintaining her dump beyond Oxmanstown Green. This green lay in the vicinity of Smithfield, so the Dog Pond may have been close to the dump’s actual location. Why it is called the Dog Pond I cannot say. Perhaps the name is a corruption of Duck Pond. When Joyce revised this passage he changed it to the Serpentine, which is a similar pond in London’s Hyde Park. As HCE’s Crime in the Park is essentially the Wake’s Original Sin, it corresponds to the Fall of Man in the Garden of Eden―which has a serpent but no dog. There are a couple of other allusions to Eden here: macadamised (MacAdam = Son of Adam) and here where race began.

The Dog Pond in the Phoenix Park

Wherever Katherine Strong’s actual dump was, it is entirely fitting that Kate Strong’s dump in Finnegans Wake is located here, where another of Dublin’s great swindles took place: Wharton’s Folly (RFW 010.21–22):

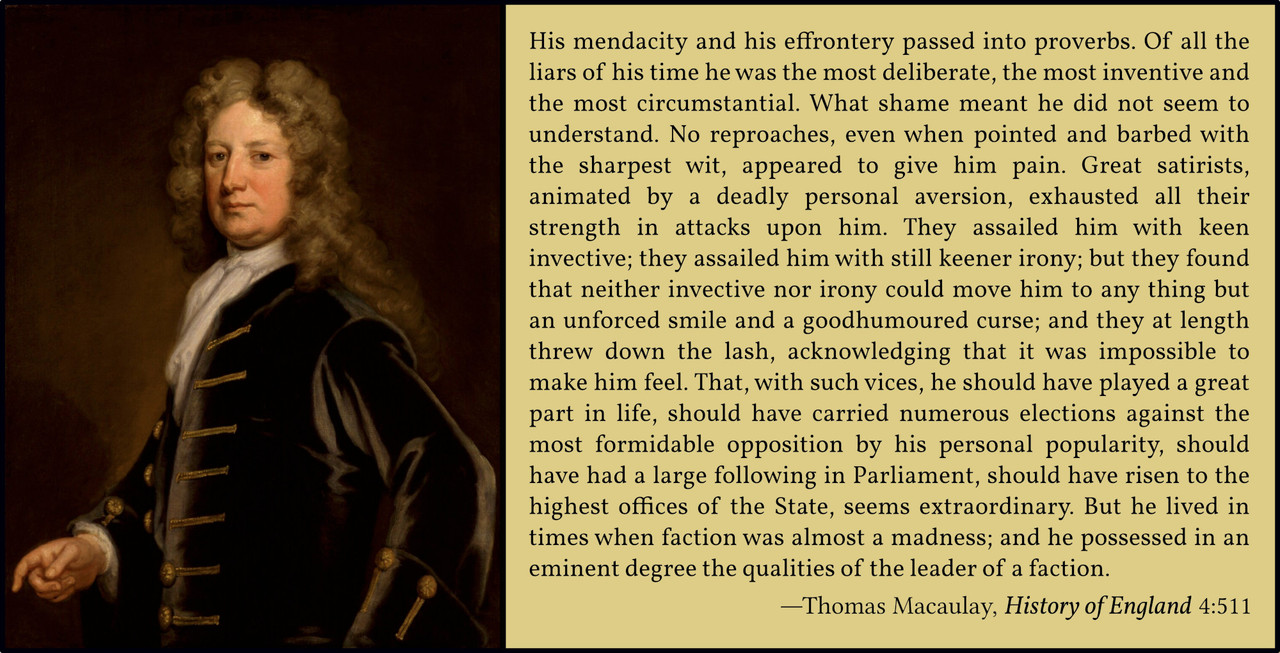

The Wharton in question, Thomas (1648–1715), who oversaw the project as Britain’s viceroy in Ireland circa 1710, was a colourful figure, even by the standards of his era. Jonathan Swift damned him, specifically, as a “public robber, an adulterer, a defiler of altars” and, generally, as “the most universal villain I ever knew”. Others considered him a man of immense charm. But such contradictions were in keeping with the age.

His Dublin fort was originally envisaged as one of four arsenals to be built around Ireland, one in each province, during the uneasy years after the Williamite Wars. Projected to cost £64,000, it would be funded by among other things taxes on alcohol and tobacco. The planned structure included two gates and drawbridges, a portcullis, and eight sentry boxes “with ornaments”. Elaborate buildings were also intended for inside the huge fort, which was 550 yards in diameter.

In the event, those never happened. But even the earthworks were gargantuan, involving 13 million cubic feet of soil. Inevitably, the project soon ran over budget, with excavation costing 60 per cent more than approved. It later emerged that there were many corrupt practices, including payment to phantom workers, bribes taken from actual workers, and horses charged for but used privately by the overseers. In a scheme that never went much further than earth movement, even the involvement of 24 overseers or assistant overseers looks excessive. But only months into the work, as Edward McParland of Trinity College ... has put it, “the political tide was washing Wharton and his Star Fort into choppy seas”.

When the Whigs he supported lost the 1710 election, the viceroy fell from favour, hard. The project engineer was soon called before the House of Commons and “by October 1710 the cat was out of the bag” on the various malpractices. Wharton’s successor recommended the work be stopped and a smaller arsenal be built instead in Dublin Castle, with a powder magazine “a little out of the town”. The Magazine Fort―a fraction of the size, although it too earned a satirical verse from Swift [RFW 010.32–34]―was constructed nearby in the 1730s. It still stands, albeit abandoned. Meanwhile, and allowing for Dr McParland’s point that the corruption involved was not unusual by 18th-century standards, it seems apt that the only trace of the Star Fort now is a hole in the ground. ―Frank McNally, The Irish Times, 2 April 2021

I think Katherine Strong and Thomas Wharton would have got on like a house on fire.

Thomas Wharton, 1st Marquess of Wharton

Hugh Lane

Another important element of this paragraph is the Hugh Lane bequest. This was foreshadowed in the previous paragraph by the words our legacy unknown.

Hugh Lane was Lady Gregory’s nephew. In 1908 he founded Dublin's Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, the world’s first public gallery of modern art. His brief entry in Adaline Glasheen’s Third Census of Finnegans Wake reads:

Lane, Sir Hugh (1875–1915)―nephew of Lady Gregory’s who offered some good paintings to Dublin, but when Dublin dragged its feet, he gave them to the Tate. When he went down on the Lusitania, he left a will, again giving the paintings to Dublin, but a legal flaw let the Tate keep them. A celebrated controversy followed. ―Glasheen 159

When Joyce wrote this paragraph, the case had not yet been settled―our legacy unknown.

-

she pulls a lane picture The Lane Bequest comprises 39 paintings, mostly French impressionists. Legally, the collection belongs to the National Gallery in London, but most of the paintings are now displayed in the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin. Since 1959 the two galleries have agreed to rotate the works between them. French tirer: to draw, delineate. A porcelain picture is created by printing a photograph onto porcelain. ALP’s initials are also encoded in a lane picture. HCE is a couple of lines below in a homelike cottage of elvanstone. This implies that Kate can be seen as an older version of ALP.

-

dreariodreama Obviously a dreary drama and a dreary dream, but with Hugh Lane it also evokes Drury Lane, home of London’s Theatre Royal (Tindall 95). The theatre underwent a major renovation in 1922. John Gordon also suggests diorama (Gordon 079.28–9).

-

as her weaker had turned him to the wall The surface meaning alludes to the saying: The weakest goes to the wall, meaning that in a crisis the weakest will be the first to be sacrificed. To turn one’s face to the wall means to accept one’s fate and die quietly. In the context of the Lane bequest, though, the phrase also suggests the custom of turning the pictures of a recently deceased person to the wall as a sign of grief or mourning. And her weaker is also Earwicker―another reminder that Kate is an older ALP.

-

hume sweet hume This variation on the phrase home sweet home may also echo Hugh Lane. To inhume means to bury, which is also relevant in the immediate context of the Viconian Cycle.

Hugh Lane and the Lusitania off the Fastnet Rock

The House by the Churchyard

Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1863 novel The House by the Churchyard is a key text for Finnegans Wake. It is set in Chapelizod, and its plot loosely revolves around an assault that takes place in the Butcher’s Wood in Phoenix Park. In Finnegans Wake this assault is combined with the Phoenix Park Murders of 1882 and the mugging of Joyce’s father John Stanislaus Joyce (Ellmann 34, 545) to create HCE’s encounter with the Cad―the Oedipal Event.

Phornix Park (at her time called Finewell’s Keepsacre but later tautaubapptossed Pat’s Purge), that dangerfield circling butcherswood where fireworker oh flaherty engaged a nutter of castlemallards and ah for archer stunned ’s turk, all over which fossil footprints, bootmarks, fingersigns, elbowdints, kneecaves, breechbowls a.s.o. were all successively traced of a mostenvolving description.

-

dangerfield Paul Dangerfield (alias Charles Archer) is the assailant. He is agent for Lord Castlemallard’s English properties.

-

butcherswood The site of the assault is Butcher’s Wood, the area of Phoenix Park immediately south of the Castleknock Gate.

Butcher’s Wood

-

firework oh flaherty Lieutenant Hyacinth “Fireworker” O’Flaherty is a member of the artillery regiment stationed in Chapelizod. He fights an abortive duel with the following. A Hyacinth O’Donnell will make an appearance later in this chapter.

-

nutter Charles Nutter, who fights an abortive duel in the Phoenix Park with Fireworker O’Flaherty. He is agent for Lord Castlemallard’s Irish properties.

-

castlemallards Lord Castlemallard, a wealthy property owner and aristocrat.

-

archer Charles Archer is Paul Dangerfield’s alias.

-

stunned’s turk In the assault, Dangerfield stuns Dr Sturk, the military physician, and leaves him for dead in the Butcher’s Wood.

-

all over which fossil footprints, bootmarks Chapter 53 has a drawing of a footprint left by Charles Nutter’s boot at the scene of the crime.

Although Kate’s testimony is mainly concerned with the latest version of the crime―which will soon be the subject of a lengthy court case―it also echoes an earlier version of the oedipal assault on HCE: the pegging of stones at his tavern in the previous chapter:

-

beggars’ bullets slang for stones.

-

the smithereen panes like the window panes of HCE’s tavern, which the pegged stones smashed to smithereens.

The House by the Churchyard, Chapelizod

And Finally

The general drift of this paragraph is not too difficult to follow. There is, however, one sentence in it that had me scratching my head. Here are its two versions, the original from 1939 and Rose & O’Hanlon’s restored version from 2010:

What subtler timeplace of the weald than such wolfsbelly castrament to will hide a leabhar from Thursmen’s brandihands or a loveletter, lostfully hers, that would be lust on Ma, than then when ructions ended, than here where race began: and by four hands of forethought the first babe of reconcilement is laid in its last cradle of hume sweet hume. ―FW 080.12–18

What subtler timeplace of the weald than such wolfsbelly castrament will hide a leabhar from Thursmen’s brandihands or a loveletter, lostfully hers, that would be lust on Ma, than there where ructions ended, than here where race began: and by four hands of forethought the first babe of reconcilement is laid in its last cradle of hume sweet hume. ―RFW 064.08–12

The Restored Finnegans Wake omits the word to before will hide, which sounds like a good emendation. But Rose & O’Hanlon also emend then when to there where, which just seems wrong. After timeplace it is surely to be expected that we will have a than then when (time) followed by a than here where (place). The first-draft of this sentence read as follows:

What safer place to hide a book from Thursmen or a loveletter from Ma than there where [BLANK] ended and race began. ―JJDA

The gist of the sentence, then, seems to be:

What better time and place to hide and preserve ALP’s Letter than Kate’s kitchen midden behind the Mullingar House, where all of human history lies buried. This midden preserves all the relics of the past: ancient Rome, the Vikings, Shakespearean literature, Vico. It was here that all of the Wake’s assaults took place, just as it was here that all of history’s pitched battles were fought. Kate’s dump lies behind HCE’s tavern. The Phoenix Park, where Katherine Strong compiled her dump, is also behind the Mullingar House. So the two dumps are one and the same, as are the two Kates.

The Dung Heap

The final clause embodies the Viconian Cycle with its three-plus-one pattern of birth, marriage, death and ricorso. The circle closes with hume sweet hume which both buries the dead (inhumation) and brings us home. The Scottish philosopher David Hume also present―he was born David Home. Hume wrote a famous History of England, but unlike Vico or Hegel he did not have a philosophy of history.

-

weald a forest or wood (like Butcher’s Wood). Also world.

-

wolfsbelly castrament Latin belli: of war and castra: military camp. The Latin elements suggest that we should follow John Gordon by identifying the wolf with the she-wolf who suckled Romulus, the founder of Rome. For most of its ancient history, Rome was little more than a huge military camp. Note that the initials are WC, hinting at the Museyroom or outhouse behind HCE’s tavern. In the previous chapter the huge chain envelope handed in was superscribed to Hyde and Cheek, Edenberry, Dubbllenn, WC (RFW 053.09 ff). The wolfberry is also known as the goji berry, but I don’t see how this could be relevant. To have a wolf in one’s belly is to be very hungry. The contents of a wolf’s belly can come out as either vomit or excrement.

-

leabhar Irish: book. The image seems to be of medieval Irish monks hiding their manuscripts from marauding Vikings who want to burn them. Also hidden from destructive hands is ALP’s Letter from Boston, Massachusetts, which is here compared to William Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost. ALP’s Letter is also the book Finnegans Wake. Kate’s midden is also a book―a history book.

-

when ructions ended Tim Finnegan’s wake was marred when a row and a ruction soon began. Presumably, it ended with Tim’s “resurrection”, which marks the point where the Viconian Cycle ends and begins again. The ructions at Finnegan’s wake represent all historical conflicts. FWEET notes allusions to both in castrament.

-

where race began With Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden (ie the Phoenix Park), where the Viconian Cycle begins.

The last four clauses are, I believe, the utterances of the Four Old Men:

Give over it! And no more of it! So pass the pick for child sake! O men!

As the Wake’s gospellers, the Four also embody the 3+1 pattern of the Viconian Cycle―the three Synoptic Gospels + St John’s Gospel.

And that’s as good a place as any to beach the bark of our tale.

References

- Joseph Campbell, Henry Morton Robinson, A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York (1944)

- Mrs A M Fraser, Katherine Strong: A Woman of Old Dublin, Dublin Historical Record, Volume 17, Number 4, Pages 143–146, Old Dublin Society, Dublin (1962)

- John T Gilbert (editor), Calendar of Ancient Records of Dublin, Volume III, Joseph Dollard, Dublin (1892)

- Adaline Glasheen, Third Census of Finnegans Wake, University of California Press, Berkeley, California (1977)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas (1963)

- Eugene Jolas & Elliot Paul (editors), transition, Number 4, Shakespeare & Co, Paris (1927)

- [James Joyce](https://archive.org/details/fi