Source: University of Texas

In the summer of 2013, I was sent to the University of Texas in Austin to research the life of Harry Houdini for a TV biopic. While perusing his collection of personal correspondence, I stumbled across the most insane letter I have ever read, sent by a woman who claimed to be “Her Royal Highness Princess Alexandra Nicholas.”

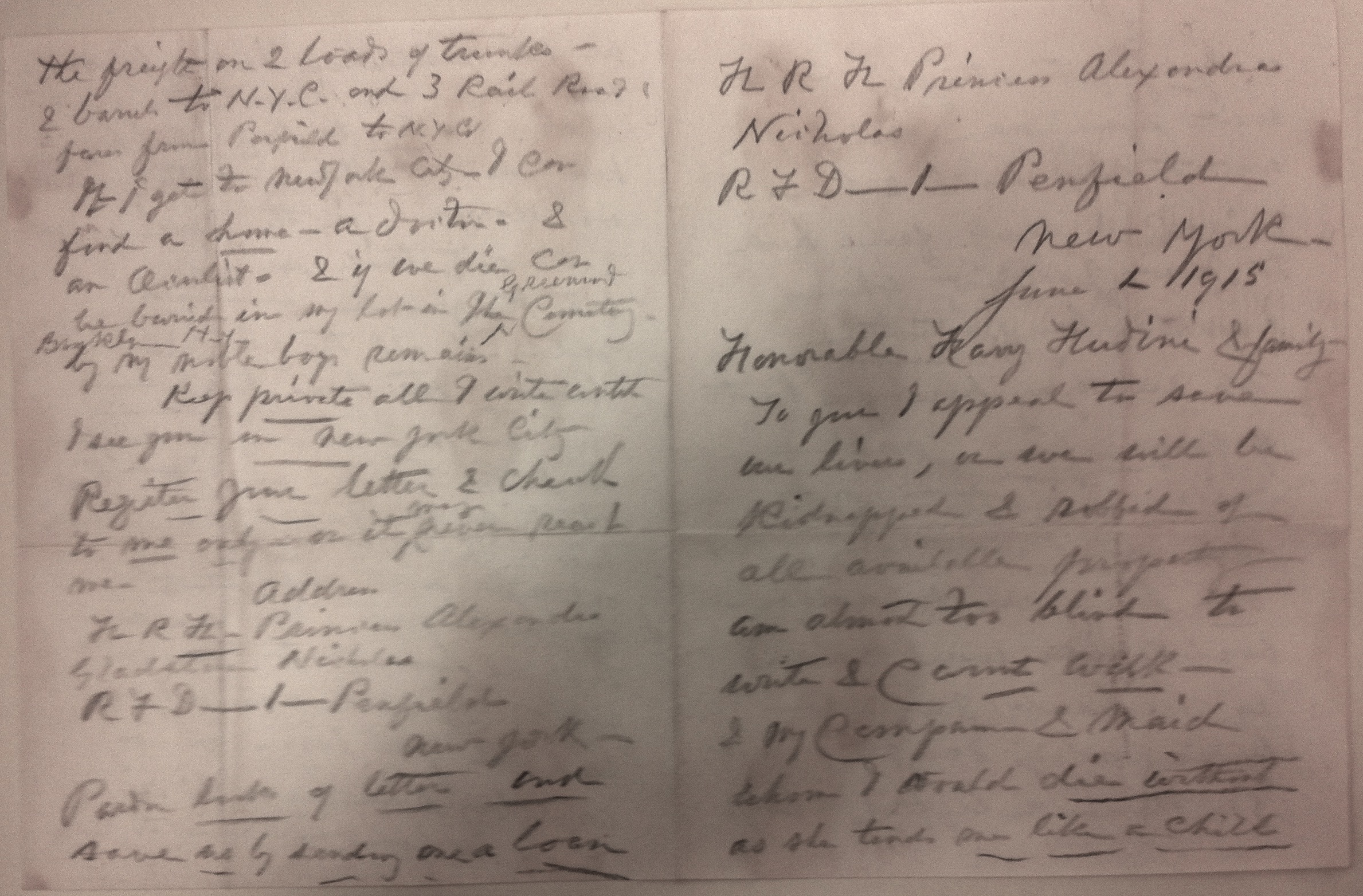

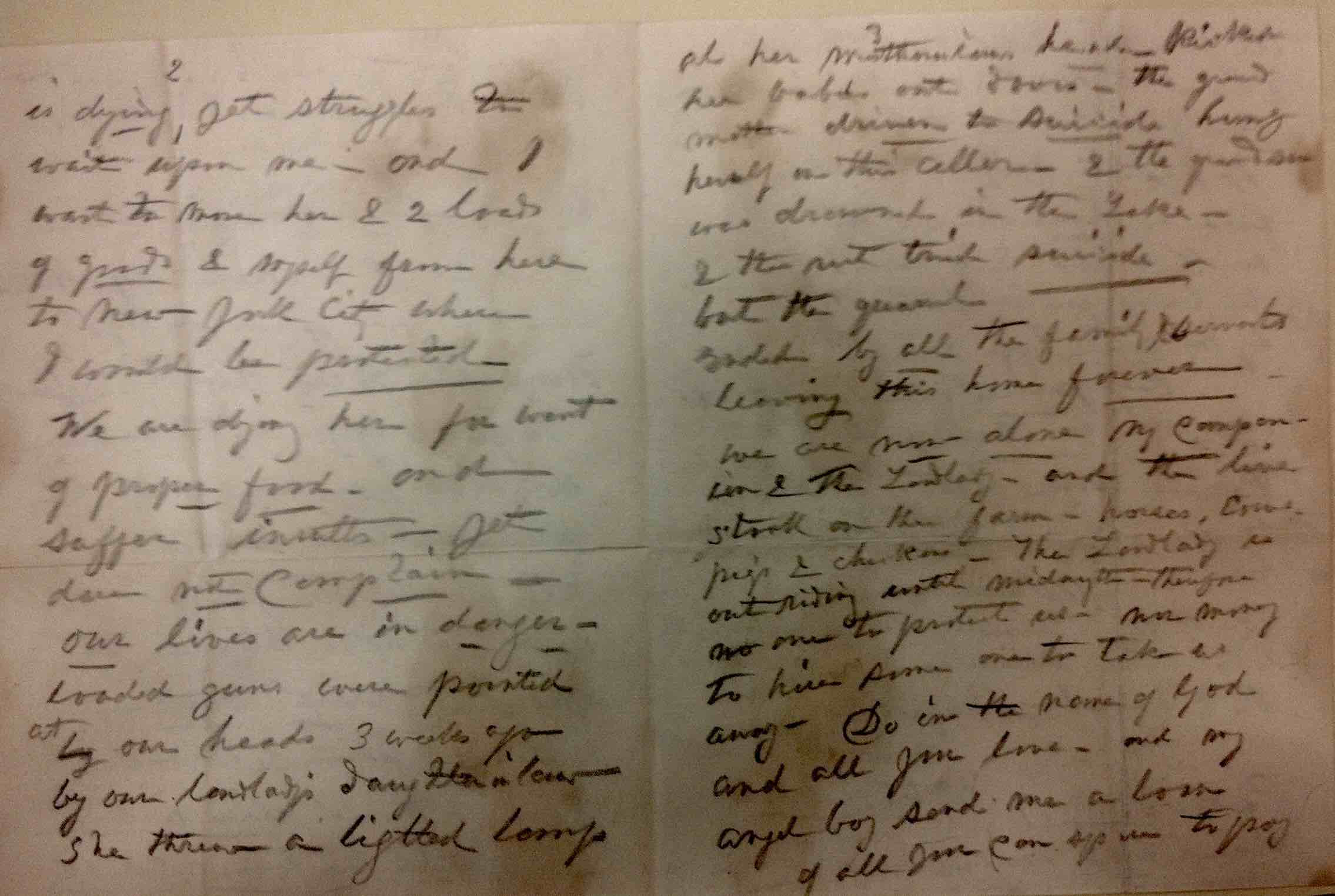

Photograph is my own, note courtesy of the University of Texas

“H R R Princess Alexandra Nicholas Honorable Harry Houdini & Family To you I appeal to save our lives, or we will be kidnapped & robbed of all available property—am almost too blind to write & cannot walk—& my companion & maid whom I would die without as she tends me like a child is dying, yet struggles to wait upon me—and I want to move her & 2 loads of trunks & myself from here to New York City where I would be protected—We are dying here for want of proper food— and suffer insults— but I dare not complain—our lives are in danger— loaded guns were pointed at our heads. 3 weeks ago by our lordship’s daughter in law— she threw a lighted lamp at her mother in law’s head—kicked her babies out doors—the grand mother driven to suicide hung herself in the cellar—& the grandson was drowned in the lake—& the rest tried suicide, but the guard —aided by all the family & friends leaving this home forever- we are now alone my companion & the Landlady—and the live stock on the farm—horses, cows, pigs & chickens— The Landlady is out riding until midday— they’re no one to protect us — nor money to hire some one to take us away—Do in the name of God and all you love—and my angel boy send me a loan of all you can spare to pay the fright on 2 loads of trunks—& board to N.Y.C. and 3 Rail Road fare from Fairfield to N.Y.C.—If I got to New York City—I can find a home—a (?) & an (?)— & if we die can be buried in my lot in the Greenwood Cemetery, Brooklyn, N.Y. —by my noble boy’s remains—Keep private all I write until I see you in New York City—Register Your Letter & write to me only or it may never reach me.”

My immediate instinct was to assume that Houdini had kept this letter for his own amusement, since he was kind of a jerk. That was until I found her obituary, dated to 1918, which Houdini had kept in a scrapbook. The newspaper stated that the woman had willed Houdini her claim to a fortune of $30 million (roughly equivalent to a half billion dollars in modern terms). Houdini professed that the woman was totally sane and that her claims were real. This was particularly meaningful because Houdini was a notorious skeptic who greatly enjoyed debunking spiritualists and con artists, with a passion bordering on vindictiveness. What didn’t make any sense to me is that most of Houdini’s major biographers have completely neglected to mention that a Russian princess willed him an absurdly large fortune, and the one book that I found that referenced the episode at all only presented it as a brief anecdote in a couple of paragraphs.

Harry Houdini, known in theatrical circles as the Handcuff King, is the proud possessor today of a legacy of over $30,000,000 willed to him by the Princess Alexandra Gladstone Nicholas, who died in Rochester over a week ago, and bequeathed to him a claim for that amount against the Government of Denmark… The legacy came to Princess Nicholas in consideration of saving the life of Gen. Carlos Butterfield, who attempted suicide in New York City about fifty years ago. The general had started a suit against the Government of Denmark for recovery of a large sum of money, claimed to be due to him through the destruction of his ship in Mexico in 1854…Houdini found the Princess in poverty and befriended her. He showed a Times reporter letters written to him by the Princess. “I never expected to get any reward for helping her,” he said, “but I know she was not demented and that the legacy is based on fact.” - The Brooklyn Daily Times, January 23, 1918

Over the following two years, I found myself periodically coming back to this letter and newspaper clipping, searching for Princess Alexandra. After scouring royal family trees, I consulted with a historian who specialized in 19th century European royal lineages, and he had never heard of such a woman. This led me down the rabbit hole into censuses, birth certificates, death certificates, baptism records, and 150 year old newspapers as I pieced together the biography of a deranged compulsive liar. At every turn I found yet another alias connected to another absurd story.

The big breakthrough came through her son, Washington Irving Bishop. He had been a moderately famous mind reader who was autopsied alive—his macabre death and subsequent murder trial had been tabloid fodder for a few years. All over this story was the outlandish behavior of his mother, who was not a princess named Alexandra, but a woman named Eleanor Fletcher Bishop. Eleanor Fletcher Bishop has been written about in a few articles and books, but mostly in relation to this incident. Oh, and there’s also a play about it, which was most recently performed in 2006 at a theater in Denver. What nobody had put together, then or now, was that Eleanor Fletcher Bishop had gone by several different aliases over the course of her life, and had been connected to several highly suspicious deaths, in addition to maybe ten or so extremely bizarre news stories. Apparently she was just so charming and beautiful that nobody noticed that she was likely a psychopath.

——————————————————

Though Eleanor claimed to be the daughter of Sir James Davison and Lady Catherine, two members of British nobility, born in either the year 1835 or 1845, records show that she was baptized in a small, working class church in Liverpool in 1832, and was the daughter of a mariner. She was adopted by a man in New York by the time she was a teenager, and was soon married off to his 59 year old brother in law. Her creepy adoptive-uncle-turned-husband, Nathaniel C. Bishop, was one of the wealthiest men in New York City—a real estate magnate and manager of the Vanderbilt fortune, among others. Their marriage was not a happy one.

Starting on her 20th birthday, Eleanor repeatedly showed up in the newspapers for one outlandish reason after another. On at least four separate occasions, she claimed that men had broken into her house to kill her. She was arrested twice on accusations of theft and fraud, and had successfully convinced judges on both occasions that she was the victim of conspiracies and that her accusers were the real criminals. Nobody seemed to doubt any of her claims.

Then there was the highly suspicious death of her husband, which I am fairly comfortable concluding she orchestrated. Eleanor and Nathaniel had been at the end of a seven year long, highly publicized divorce, after Nathaniel had run off with his mistress a couple of times. (His unfaithfulness absolutely outraged the society pages.) In the days before his death, Nathaniel gave away his remaining fortune, and left no will other than asking that Eleanor not be allowed to attend his funeral. He soon died after a very short and mysterious illness; his safe found robbed of all of its valuable documents. Not one to be dissuaded by Nathaniel’s dying wish to stay away from his funeral, Eleanor showed up and threw a fit, going so far as to actually jump into his grave with him. When his body was exhumed, the doctors noted something particularly suspicious:

“The wonderful preservation of the body, and the appearance of the flesh, which was of a reddish color, surprised the experienced spectators, and comments were freely interchanged. No appearance of decomposition could be detected, and the body looked as if it had just been taken off ice. The undertaker remarked that if the body had been subjected to an embalming process the work of preservation could not have been so successfully performed. Drs. Wood and Shine unhesitatingly expressed the opinion that the body presented all the appearances of arsenical poisoning.” - The New York Times, Apr. 12, 1874

Somehow, nobody thought to look into the matter further. Eleanor continued to ostentatiously mourn the husband that she had absolutely despised by all accounts.

It was some years after Nathaniel’s death that their son, Washington Irving Bishop, was autopsied alive after collapsing from an equally mysterious and short illness. Eleanor wrote a book about her harrowing experience as a mother mourning her son’s death and spoke in impassioned speeches throughout the murder trial. Though the doctors that performed the premature autopsy were ultimately convicted, I have a theory that Eleanor had poisoned her own son for attention, causing the coma that imitated death. Perhaps that sounds extreme, but it would not be the last time she murdered her own child and feigned victimhood.

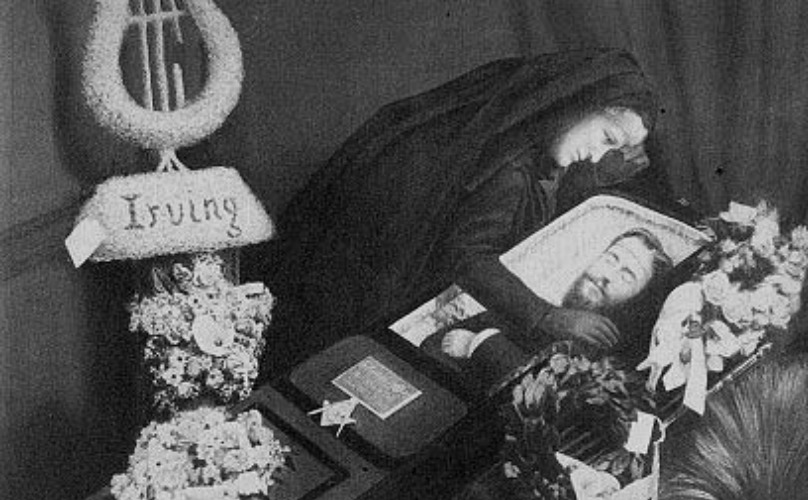

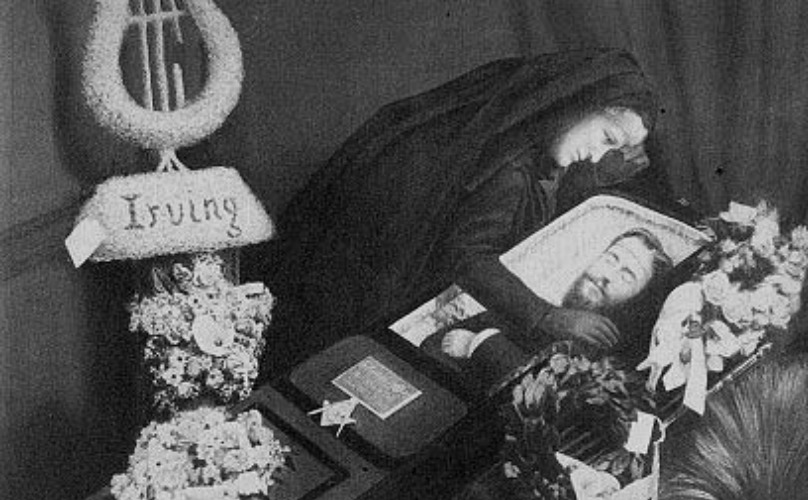

Eleanor Fletcher Bishop’s glamour shots with her son’s prematurely autopsied body. Source: University of Texas

After the death of her husband and son, the destitute woman came up with various accounts of her life and periodically changed her surname. She swindled other people for money by putting on charity events for herself, claiming to be a Countess who had fallen from grace after a series of unfortunate events; a perpetually victimized woman who nursed Civil War heroes back to life, giving herself the monicker “Florence Nightingale of America.” (Generally, that epithet belongs to Clara Barton, the woman who founded the American Red Cross; incidentally, they were apparently friends, as they corresponded regularly, and Eleanor managed to convince Clara to send her money from time to time.)

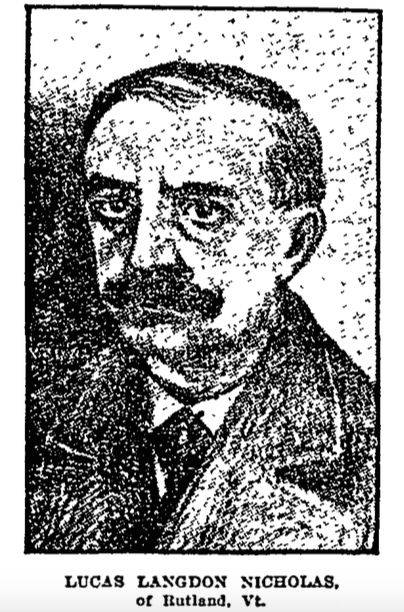

In 1893, the 61 year old woman married Lucas Langdon Nicholas, then 43 years old. Eleanor and Lucas separated after a few weeks, deciding that the whole thing was a bad idea, but never bothered to get divorced. It was by this husband that she claimed that she was the rightful heiress to the Russian throne. The two of them both provided a far-fetched story about Lucas and his brother being abandoned in Greece by his royal parents as an infant; in fact, his birth certificate shows that he was born in Brooklyn.

Lucas Langdon Nicholas - Source: Proquest

Even if Eleanor had no hand in either her first husband or her son’s death, she almost certainly escalated to manslaughter later in life. She adopted three Swedish children, whom she also claimed were heirs to sizable fortunes in Europe. Eleanor promptly sent two of them away to an orphanage, but kept the youngest—a 22-month-old baby. The child was forcibly taken away from her due to accusations of neglect. He died the very next day.

In her old age, Eleanor claimed more and more far-fetched lies that everyone just seemed to believe. The people who knew her were entirely convinced that she was the Russian princess Alexandra Nicholas and a cousin of the Prime Minister of England to boot. In October of 1913, she made an appearance in the newspapers again when she allegedly sent a tarring and feathering mob to Dr. Mary Walker after they had some petty argument (apparently, tarring and feathering still happened in the early 20th century).

Source: Chicago Daily Tribune

“Youthful marauders made a bold attempt last night to tar and feather Dr. Mary Walker at her home at Bunker Hill… a party of young men from Oswego went to the doctor’s barn and with a lighted lantern tried to entice her to leave the house… she escaped the grasp of a would-be captor and slammed the door…the mob had disappeared leaving nothing but a pot of tar and a feather pillow… Dr. Walker [says] the attack was instigated by Princess Alexandra Nicholas. The princess, who is Russian, came to Dr. Walker’s home from Rutland, Vt. several weeks ago for medical treatment… The princess denies she was connected with the attack.” - Chicago Daily Tribune, Oct 26, 1913

It was two years later that Harry Houdini befriended her and gave her enough money to live out the remaining three years of her lonely and completely fabricated life.

Oh—and what about this $30 million fortune that she willed to Houdini? Well, oddly enough, after spending a ridiculous amount of time wading through legal documents from the 1880s, I did indeed find an unresolved law suit between the United States government and the governments of Mexico and Denmark on behalf of Carlos Butterfield, for exactly the reason that “Princess Alexandra” had provided. The claim was not for $30 million but $1 million and some change—still a very large fortune. I have no good explanation as to how she somewhat accurately came up with a story about an obscure law suit that had, in fact, occurred decades before, although I think it’s safe to assume that she had no claim to it in the first place.

——————————————————

This article originally appeared on HistoryBuff.com, which has sadly since shut down. I have reposted it to my blog with the generous permission of the editor.