Un saludo afectuoso, Hivers, amigos!

En especial para la comunidad PhotoFeed**!! **

Fundación

El mercado

La artesanía

La emigración árabe

A modo de conclusión

✧・゚ PoetaFranko ・゚✧

Warm greetings, Hivers, friends, especially for the PhotoFeed community!!

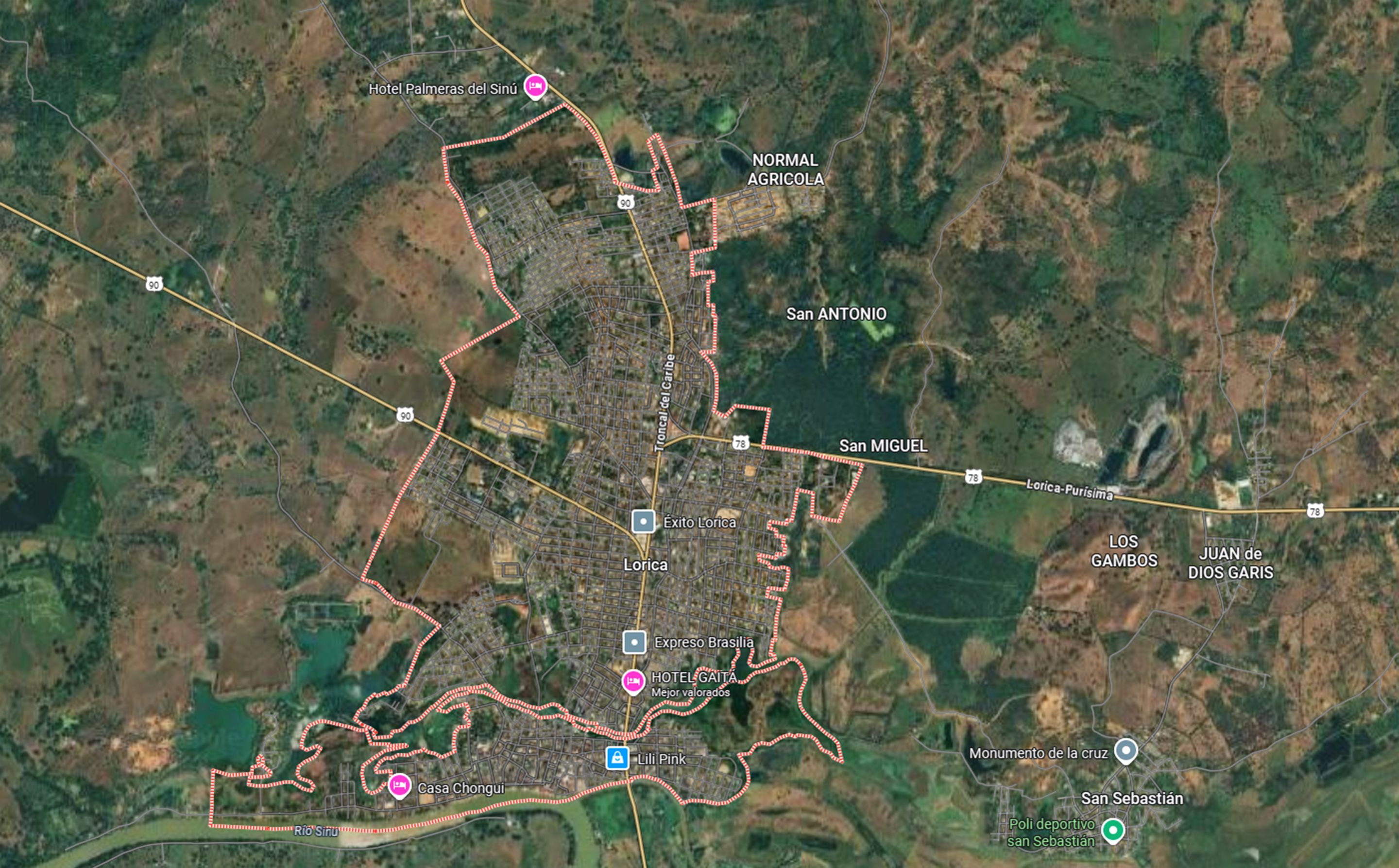

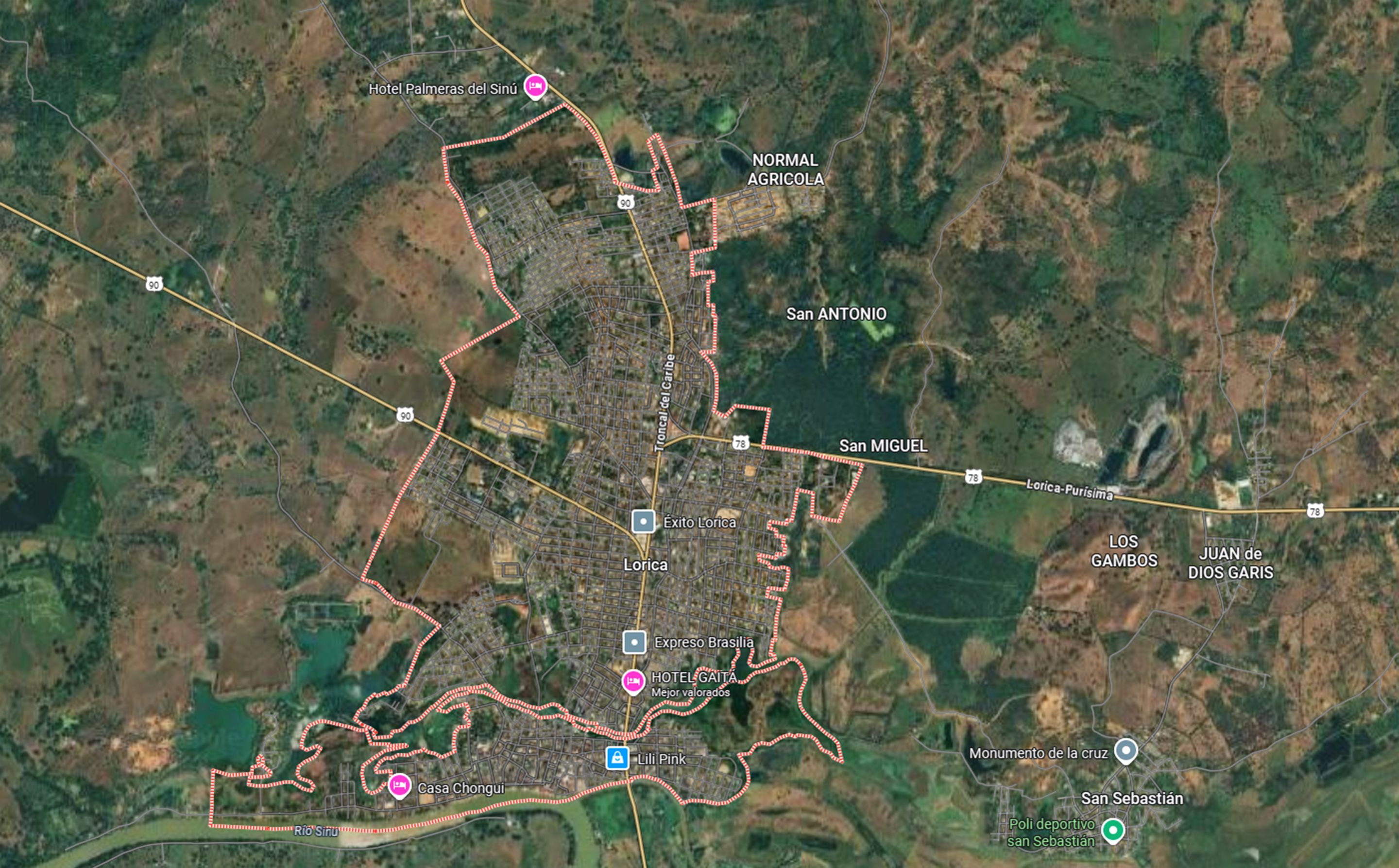

In recent days, we let ourselves be carried by the warm winds of the Colombian coast and found our way to Lorica, a city I had promised to write about before.

Santa Cruz de Lorica—this jewel of Colombia—rests on the banks of the Sinú River as if the water had entrusted it with a secret, one it keeps hidden in its streets and timeless buildings. Known as the Capital of Bocachico, to me it is also a city steeped in memories, swaying to the gentle rhythm of the current.

Along its streets, the sun lingers tenderly on colorful facades, gracefully aged by time. The public market—its beating heart—throbs with the rhythm of voices, the clinking of cutlery, and the laughter of visitors. It is a living poem, where the aroma of fresh-caught fish mingles with the scent of fried delicacies and the sweetness of tropical fruits.

In its earliest days, Lorica was little more than a scattering of isolated families—settlers who resisted the colonial hacienda system, preferring instead to live in palenques, communities for escaped slaves. It was not until the late 18th century that families began to gather and form a true settlement, united by agricultural production, livestock raising, and craftsmanship.

According to Sandra Reina Mendoza, in Banrepcultural.org, a thatched-roof chapel was built in 1754, and by 1772 work had begun on a stone chapel. Around 1776, Antonio de la Torre y Miranda persuaded the inhabitants to relocate to higher ground, prompted by the frequent flooding of the nearby marsh bearing the same name.

Wikipedia records that Santa Cruz de Gaita, as it was then known, was officially founded on May 3, 1776, by the governor of Cartagena, Don Juan de Torrezar Díaz Pimienta, who assigned the task to cavalry lieutenant Don Antonio de la Torre y Miranda. The lieutenant entered the region through what is now San Bernardo del Viento, following the Aguas Prietas stream to its confluence with the Sinú River. There, he was welcomed by numerous Zenú Indigenous people, who were friendly and posed no threat to the Spanish delegation’s mission of founding the new settlement.

The market

Inside the market, tucked beside the food stalls, I came across a cozy café. On its walls hung a portrait of David Sánchez Juliao, gazing out as if ready to share his stories in a hushed, knowing voice. This master storyteller, also a son of Lorica, infused his tales and chronicles with the charm, humor, and mischief of the Caribbean, capturing the traditions, oral heritage, and history of this corner of Colombia’s coast.

The market itself is alive with flavor. Two neat rows of food stalls bustle with cooks and their helpers, each preparing the region’s beloved dishes. Here, the star is the famed bocachico, a river fish with an exquisite taste, served either fried to golden perfection or in viuda—salted, dried, and gently steamed. Alongside it, you’ll find black river tilapia, catfish, and the seasonal moncholo (or guavina), known scientifically as Hoplias malabaricus. The accompaniments are no less tempting: yuca, crispy patacón, fresh seasonal salads, creamy payasito (Russian) salad, and fragrant coconut rice—though I confess it’s not to my taste—along with bean rice and a seemingly endless variety of regional specialties.

Craftsmanship

In the surrounding streets—and even within the market itself—you’ll find handicrafts born from the faith and dedication of the region’s artisans. Faith, because each piece carries the hope of being chosen, mostly by Colombian tourists and, more occasionally, by foreigners passing through Lorica.

The variety is as wide as it is beautiful: clay pottery, cattail weavings, arrow cane, fine threads, and supple leather worked into pieces both practical and ornamental. Among them stands the iconic sombrero vueltiao, woven from arrow cane—the emblematic Colombian craft, the very hat Gabriel García Márquez wore when receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature. Around it, the stalls bloom with sandals, riding saddles, bracelets, necklaces, mats, rugs, dresses, cushions, and the famed goat-hair backpacks of the Wayuu people—though not native to this region, their replicas, made from equally prized materials, are crafted here with great skill.

Art, too, thrives in the market square. There, paintings abound, and one name stands out: Marcial Alegría Garcés, a local artist who embraced primitivist painting and whose works have reached more than 18 countries. His canvases captured the life of the peasant, the enchantment of the region in vivid colors, and the joy that defines the people of Lorica. Today, new generations of painters follow in his footsteps, continuing to portray the magic and soul of this place.

Arab Emigration

Lorica is not the capital of Córdoba, yet it carries the dignity of a city that has lived many lives. In the late 19th century, Syrians and Lebanese arrived, bringing with them their accents, their skilled hands, and their flavors. Here, a mestizaje was born—not one recorded in textbooks, but preserved in the living memory of its people. The Arabs—called “Turks” by locals—left a mark that still shapes the region. Their legacy is visible in the elegant buildings surrounding the main park, in the architecture along the streets, and in the city’s commerce, where many of their descendants continue to thrive.

They began arriving in the second half of the 19th century, fleeing wars in Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon. Lorica offered them more than refuge—it offered opportunity. The Sinú River, wide and navigable, became their gateway. Around 1870, steamboats such as the Bolívar, Sinú, María, Colombia, and Damasco connected Cartagena with Tolú, Coveñas, Lorica, San Pelayo, and Cereté. These journeys, made twice a year and lasting about 25 hours, fueled regional growth, expanded trade, and consolidated the power of large estates and landowners—prime customers for the Arab merchants, who brought goods first by sea, then by river, to the banks of the Lower Sinú, where their communities took root.

To Conclude

In closing, I cannot fail to mention Manuel Zapata Olivella—writer, doctor, and tireless traveler—whose masterpiece Changó, el gran putas is a literary drumbeat that crosses centuries and oceans, vindicating the African heritage and the deep pulse of these lands.

My visit was brief, yet long enough to understand that Lorica is not merely a place you see—it is something you drink, like a sip of warm river water, which then flows within you, unhurried, as if it knew it had all the time in the world. I promise to return with more time, perhaps to wander deeper into the details of this extraordinary town, chasing the stories that slip through the breeze and hide along its docks.

For now, I leave with the certainty that Lorica is an open book—one that writes a new page every time it is read.

Thank you for reading. I hope you enjoyed this journey, and may the rest of your day be wonderful.

PoetaFranko

Thanks for visinting!! 🌼

✧・゚ PoetaFranko ・゚✧

Photographs by/Fotografías de: Hive Account /@poetafranko

Device/Dispositivo: Samsung A56

Digital Edition / Edición en Adobe Photoshop

Únete a nuestra comunidad de creadores de contenido haciendo clic en mi [Enlace de Referido]

(VOTA POR EL TESTIGO DEL PROYECTO BBH WITNESS)

👉VOTE FOR THE BBH PROJECT WITNESS

created by @bradleyarrow

created by @bradleyarrow