Two planets, Urras and Anarres, so close that each is the other’s moon, centuries into the future.

Urras is very similar to Earth in both its natural environment and political structure: there are two major powers; one is capitalist-statist, the other socialist-statist. They don’t confront each other directly but through wars in smaller, weaker countries.

Anarres, the protagonist’s home, is a planet with only a few areas of life, sparsely populated: it is inhabited solely by the descendants of anarchist settlers who left Urras— with the consent and help of its equivalent to the UN— to found and live out their anarchist utopia, with both planets' populations kept separate, except for a few trade ships that carry minerals mined by the Urrasti and manufactured goods produced by the Anarresti. For the people of Anarres, Urras is the land of property, including the socialist country, because it is still archist and has even more centralized power than the capitalist one.

Shevek, the protagonist, is a very important physicist—so much so that he has received an invitation from a university on Urras to go there. The first chapter, with him at age 36, depicts his departure on the usual trade ship, which results in a death caused by a stone thrown by an Anarresti protester of the bunch that came to confront him directly and call him a traitor. Shevek wants his people to come out of isolation, to increase relations between Urras and Anarres.

The book is structured in alternating chapters set on Anarres and Urras, but the ones located on Anarres are analeptic (flashbacks). They recount Shevek’s past, from childhood up to the moment he decides to go to Urras, showing how his circumstances evolved and led him to make that decision. The chapters set on Urras show him as an explorer of this “new world,” learning how it truly functions while also teaching others about Anarres. Events unfold more slowly on Anarres, so dividing the story into these two chronologies was a smart narrative choice.

And behind it all lies one of the main motivations for his journey: Shevek’s great theoretical physics project—a unified theory of time, the unification of simultaneity and sequentiality. The book doesn’t go into the mathematics, though Shevek develops them; instead, it presents the philosophical reasoning that forms the basis of his theory. In this, the ideas of an ancient Terran named Ainsetain (ring any bells?) play an important role.

I really liked Shevek. He’s a curious scientist, highly rational but not cold, even though his personality is deeply introverted and solitary. I especially liked him more than the protagonist of The Left Hand of Darkness, Genly Ai, who ends up being a rather passive observer (albeit coherently so, given his role as an ambassador), whereas Shevek is much more active—calmly so—but determined to change things in both Urras and Anarres. His relationship with his partner (his “wife” in Urrasti terms) is also very well portrayed.

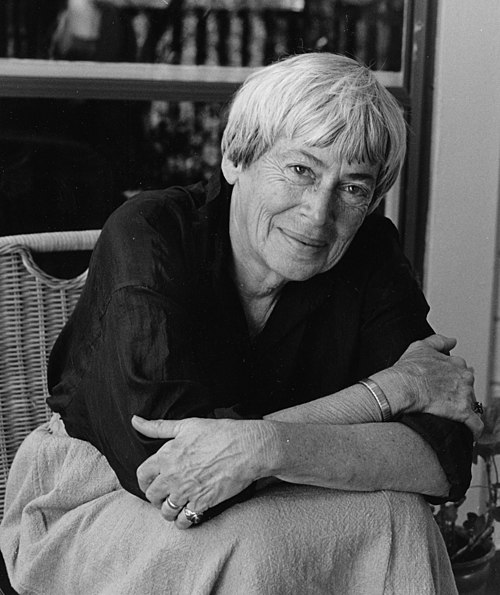

Le Guin does a great job of constructing different common senses for Urras and Anarres, and of showing how each of these worldviews harbors false prejudices about the people of the other planet. Even though the author is an anarchist, the book cannot be reduced to mere propaganda for that philosophy—as the English subtitle already hints: an ambiguous utopia. In short, it shows that there are good and bad things on both planets.

Things on Urras are not as bad as the Anarresti believe, and Anarres doesn’t work as smoothly as most of its inhabitants think. Although there are no legally formal hierarchies, informal ones and functional authorities arise and reproduce them. For instance, Shevek is the great thinker, but the physicist Sabul reaps the rewards—partially or wholly—of his work. Shevek puts up with it because he needs Sabul’s approval to publish, even if there’s no legal obligation. His mother also says that the Institute is a place where people play power games. And there are other examples showing that the largest bureaucratic body, which coordinates production, has grown conservative and overly influential, under the excuse of protecting the social organism.

Though the term isn’t mentioned, it seems that the iron law of oligarchy has appeared; a bureaucracy has gained power and become rigid, stifling progress—and Shevek challenges the situation.

Even though I didn’t find the novel’s ending entirely satisfying (it leaves you too curious about how things continued to unfold) and perhaps the final steps leading up to that point weren’t the strongest, I still consider this a great work of social science fiction—with a remarkable protagonist and outstanding world-building: one planet representing certain aspects of our own, and the other imagining an anarchist society. A physicist in two very different social worlds gives us a powerful story, rich with opportunities for reflection and comparison with reality.

Some of my favorite quotes from the novel:

[Shevek] Suffering is the unavoidable condition of life. And when it comes, one recognizes it. One recognizes it as the truth. Of course, it’s good to cure illness, to prevent hunger and injustice, as the social organism does. But no society can alter the nature of existence. We cannot avoid suffering. This pain and that pain, yes... but not Pain itself. A society can only alleviate social suffering, unnecessary suffering. The rest remains.

[Narrator, from Shevek's point of view] The idea, by its very nature, needs to be communicated: written, explained, carried out. Like grass, the idea seeks the light, loves crowds, moves among them, is enriched by them, grows stronger when it is trampled.

[Shevek]“A lifelong union is contrary to Odonian ethics.” [Gimar replies] “What’s wrong is possession; sharing is good. What more can you share than your whole person, your entire life, every night and every day?”

[Shevek, on sharing without thanks, which are for gifts] “I thought you were sharing them with me. Were they a gift? We only say thank you for gifts, in my country. Everything else we share without words, you see?”

[Bedap, Shevek’s friend] “It’s always easier not to think for yourself. To find a nice, safe hierarchy and settle into it. Not to change anything, not to risk being censured, not to upset your syndic. Letting yourself be governed is always more comfortable.”

My next novel to be read by Le Guin shall be The word for world is forest

Translated with ChatGPT