San Cristóbal de las casas

Después de nueve fantásticos meses en Guatemala, el país empezaba a parecernos pequeño. Desde el Río Dulce, donde acabábamos de cerrar la venta de nuestro velero, la atracción del país vecino, México, se hacía cada día más fuerte. Nuestro primer destino era San Cristóbal de las Casas, en el corazón del Alto Chiapas, sobre el que muchos nómadas digitales que conocimos hablaban con gran admiración. El viaje por sí solo podría dar lugar a todo un relato, pues estábamos en una de las rutas de la migración clandestina que suben desde Honduras hacia el supuesto eldor ado norteamericano. Sin buscarlo, nos vimos confrontados con esa realidad. Pero ese no es el tema, y una semana después de haber dejado el Río Dulce nos encontrábamos en un taxi colectivo que nos llevaba desde Palenque, donde hicimos una parada, hacia San Cristóbal de las Casas. Teníamos la esperanza de encontrar allí una ciudad multicultural, rica en historia y tradiciones, una ciudad fascinante.

* * * * *

Una ciudad de múltiples facetas

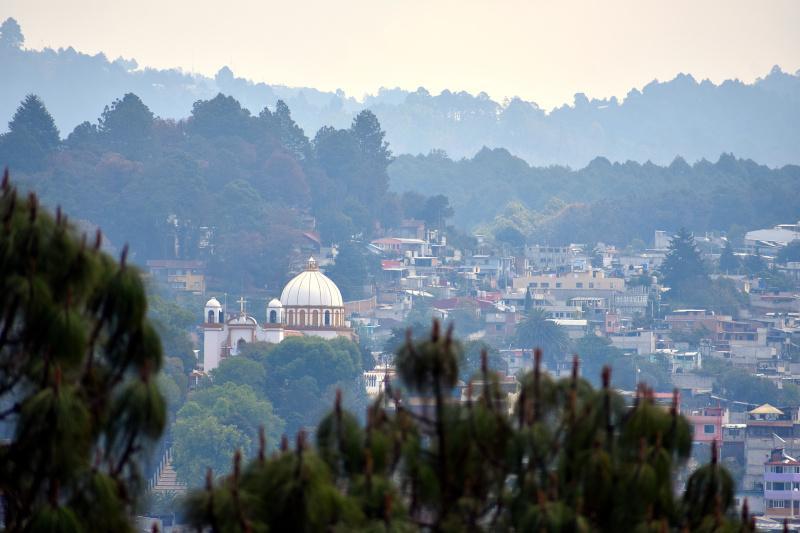

San Cristóbal de las Casas está construida en un cráter; se accede desde lo alto con vistas vertiginosas. La ciudad se extiende en silencio bajo un cielo de niebla y tejados rojos. Las callejuelas adoquinadas parecen remontar el tiempo. Los balcones rebosan geranios. Nos alojamos en una casa colonial en el barrio de Guadalupe, con una hermosa vista a la montaña. Una chimenea acogedora, muy útil, pues no esperábamos que hiciera tanto frío por las tardes. Doña Teresa, la propietaria, nos recibió con un chocolate caliente espeso como una promesa.

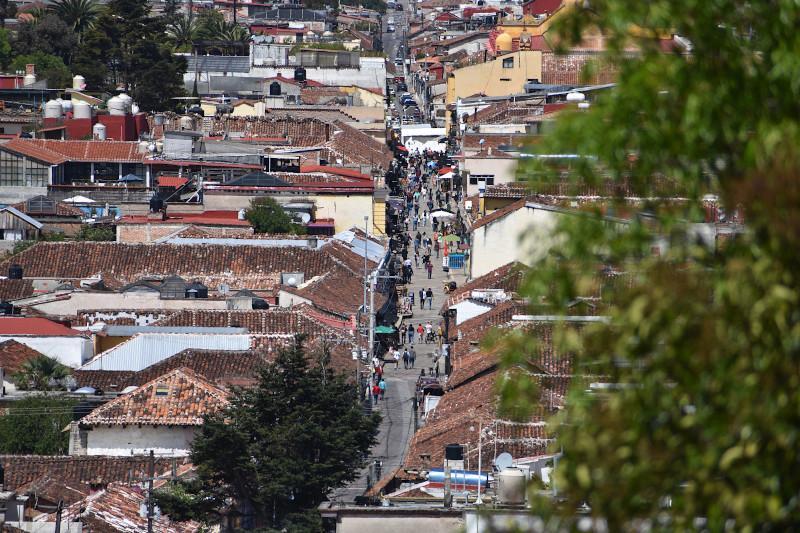

San Cristóbal se descubre a pie, con la mente y el corazón abiertos. Cada mañana bajaba por la Calle Real de Guadalupe, paseando entre cafés, galerías de arte y pequeños puestos de huipiles bordados a mano. La ciudad es un entrelazado de culturas: colonial, indígena y rebelde. Aquí todo se habla: castellano, tzotzil, silencio. De vez en cuando me sentaba en los escalones de la catedral, en la plaza central azotada por el viento y rebosante de música. Las campanas repicaban mientras niños de mejillas quemadas vendían pulseras coloridas.

El número de museos y lugares de interés parecía infinito. Nos perdimos en las salas del Museo Na Bolom, antigua morada de la cultura lacandona; visitamos el Centro Textil del Mundo Maya, discreto y conmovedor; contemplamos la iglesia de Santo Domingo, una obra maestra barroca… Alrededor, el mercado artesanal rebosa textiles, incienso, collares de ámbar y voces ancestrales. Los bordados varían según el pueblo: Zinacantán, Chamula, San Juan Cancuc. Cada hilo cuenta una cosmogonía.

Una gastronomía por descubrir

Otra forma de enamorarse de San Cristóbal. Por la mañana tomaba café de montaña, negro y denso, cultivado en laderas boscosas de pueblos tzeltales. A veces, añadíamos una gota de miel de altura o una pizca de cacao rallado, como lo hacían los mayores. En las calles, los vendedores ambulantes ofrecían jugo de naranja recién exprimido. En el mercado probábamos tamales envueltos en hojas de plátano o maíz, algunos rellenos de mole dulce con especias, otros con chipilín, esa hierba verde y suave; sopa de pan con aromas de ajo y cilantro; quesadillas azules elaboradas en el mercado por manos pacientes. Por la noche, nos quedábamos en las cocinas populares, donde las recetas pasan de madre a hija: el mole chiapaneco, espeso, oscuro y misterioso, con matices de canela y chile; tacos de huitlacoche, ese maíz negro aterciopelado; caldos humeantes de calabazas ancestrales, servidos con tortillas aún calientes. Hay que probar el pozol, bebida indígena fría hecha de maíz y cacao. Finalmente, el chocolate artesanal, a veces mezclado con chile, a veces con pétalos de rosa seca.San Juan Chamula

Una mañana tomamos un colectivo hasta San Juan Chamula, ese pueblo tzotzil donde la tierra parece más antigua. Allí, la iglesia no se parece a ninguna otra. La iglesia de San Juan Bautista se alza como enigma blanco y verde, enmarcada por banderas que danzan al viento. En su interior no hay nada fijo: no hay bancas, solo un suelo cubierto de agujas de pino, cientos de velas titilantes, y un perfume intenso a resina, humos y vida. Familias enteras murmuran oraciones a los santos, cuyas estatuas están vestidas con espejos y cintas de colores. Gallinas vivas, huevos, refrescos, rituales susurrados en tzotzil: todo aquí forma parte de una espiritualidad vibrante y animista, donde el catolicismo no es más que un velo colocado sobre mundos más antiguos. La entrada es libre, pero está estrictamente prohibido tomar fotos, como si estas pudieran robar el misticismo que permea el lugar.

Zapatistas

Subí a pie hasta el Cerro de San Cristóbal y luego al Cerro de Guadalupe, las dos colinas que guardan la ciudad como dos brazos extendidos. Son parte de comunidades zapatistas donde la entrada está controlada: hay que presentarse y obtener autorización. A pie y solo, es posible, a diferencia de lo que se suele decir. Se requiere paciencia y respeto. Aquí la tierra no se posee, se protege. Es fundamental visitar los caracoles (Caracol = caracol): núcleos de gobernanza autónoma, corazones comunitarios donde late aún la rebelión serena e inquebrantable del Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional. Los llaman así porque el caracol simboliza la escucha pausada, la paciencia, la espiral del mundo. En la entrada, un portal pintado proclama: «Entramos en un territorio rebelde. Aquí manda el pueblo y el gobierno obedece». Hay varios Caracoles: Oventic, La Realidad, La Garrucha, Morelia, Roberto Barrios… cada uno representa una región zapatis ta y una comunidad autónoma. Son lugares vivientes: escuelas, clínicas, casas de mujeres, consejos de buen gobierno. Nada aquí es decorativo, todo es necesidad.Los zapatistas no son una leyenda del pasado. Están aquí, vivos, discretos, tenaces, y su lucha no se limita a la insurrección de 1994. Construyen, día tras día, otro mundo al margen del nuestro, un mundo sin patrón, sin partidos, sin promesas electorales. Un mundo tejido de colectividad, dignidad y organización horizontal.

San Cristóbal es una mezcla de colores, luchas y oraciones suspendidas. Un mes en San Cristóbal es un mes fuera del tiempo. Un mes de altitud e historia. Este cruce de culturas que resisten sin desaparecer es un encanto para quienes aman la diferencia. Uno de los lemas pintado en las paredes ilumina su complejidad: «Un mundo donde quepan muchos mundos.»

In the Heart of High Chiapas

After nine fantastic months spent in Guatemala, the country began to feel small to us. From Río Dulce—where we had just finalised the sale of our sailboat—the pull of neighbouring Mexico grew stronger by the day. Our first destination was San Cristóbal de las Casas, at the heart of High Chiapas, a place many digital nomads we met spoke of with great admiration. The journey itself could fill an entire book, as we were on one of the clandestine migration routes that leads from Honduras to the so‑called North American El Dorado. Unintentionally, we confronted this reality. But that’s another story. A week after leaving Río Dulce, we found ourselves in a shared taxi driving from Palenque—where we had stopped—to San Cristóbal de las Casas. We hoped to discover a multicultural city brimming with history and traditions, a truly fascinating place.

* * * * *

San Cristóbal is a blend of colours, struggles, and suspended prayers. A month in San Cristóbal is a month outside of time. A month of altitude and history. This crossroads of cultures that resist without disappearing is a wonder for those who love difference. One of the slogans painted on the walls illuminates its complexity: “A world where many worlds fit.”

On the final morning, the mist was so thick we could no longer see the mountains. San Cristóbal reveals itself if you accept not to understand everything. We then departed for Oaxaca.

A City of Many Facets

San Cristóbal de las Casas sits within a crater, reached from above with a breathtaking view. The city unfurls silently beneath a misty sky and red-tiled roofs. Its cobbled streets feel as though they flow backward through time. Balconies overflow with geraniums. We stayed in a colonial house in the Guadalupe neighbourhood, with a beautiful mountain view. A cosy fireplace—very useful, as we hadn’t expected the evenings to be so cool. Doña Teresa, our host, welcomed us with a hot chocolate as thick as a promise. San Cristóbal unfolds on foot, with an open mind and heart. Every morning, I strolled down Calle Real de Guadalupe, wandering among cafés, art galleries, and stalls selling hand‑embroidered huipiles. The city is a tapestry of cultures: colonial, indigenous, and rebellious. Here, everything speaks: Spanish, Tzotzil, and silence. I sometimes sat on the cathedral’s steps, in the central square battered by wind and alive with music. Bells rang out while children with sunburned cheeks sold colourful bracelets. The number of museums and sites of interest seemed endless. We got lost in the rooms of the Museo Na Bolom, former home of the Lacandon culture; we visited the discreet yet moving Mayan Textile Centre; we admired Santo Domingo Church, a baroque masterpiece… Around, the artisan market overflowed with textiles, incense, amber necklaces, and ancestral voices. Embroidery designs vary by village—Zinacantán, Chamula, San Juan Cancuc—each thread narrates a unique cosmogony.A Gastronomy to Discover

Another way to fall in love with San Cristóbal. In the morning, I drank mountain coffee—black, dense—grown on forested hillsides in Tzeltal villages. Sometimes we added a drop of high-altitude honey or a pinch of grated cacao, as the elders used to do. In the streets, vendors offered fresh-pressed orange juice. At the market, we tasted tamales wrapped in banana or corn leaves—some filled with sweet, spiced mole, others with chipilín, that soft green herb; sopa de pan scented with garlic and coriander; blue quesadillas made by patient hands. In the evening, we lingered in cocinas populares, where recipes are passed from mother to daughter: Chiapanecan mole—thick, dark, mysterious, with hints of cinnamon and chilli; huitlacoche tacos, that velvety black corn fungus; steaming squash‑based broths, served with still-warm tortillas. Don’t miss pozol, an indigenous cold drink made from maize and cacao. And finally, artisan chocolate, sometimes infused with chilli, sometimes with dried rose petals.San Juan Chamula

One morning we took a colectivo to San Juan Chamula, that Tzotzil village where the earth seems more ancient. There, the church is like no other. The Church of San Juan Bautista rises as a white-and-green enigma, framed by flags that flutter in the wind. Inside, nothing is fixed: no pews, only a floor of pine needles, hundreds of flickering candles, and a thick scent of resin, smoke, and life. Families whisper prayers to saints whose statues are dressed in mirrors and colourful ribbons. Live chickens, eggs, sodas, and whispered rituals in Tzotzil—all participate in a vibrant, animist spirituality where Catholicism feels like a veil draped over older worlds. Entry is free, but photography is strictly forbidden, as if pictures could steal the mystique that reigns there.The Zapatistas

I hiked up to Cerro de San Cristóbal and then to Cerro de Guadalupe, the two hills that guard the city like open arms. They belong to Zapatista communities where entry is monitored—you must register and get permission to pass. It is doable alone and on foot, contrary to what one might hear. It requires patience and respect. Here, land is not owned—it is protected. Visiting the Caracoles is essential ("Caracol" means snail): autonomous governance centres, community hubs where the quiet, unbreakable rebellion of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation pulses. They are named after the snail because it symbolizes slow listening, patience, and the spiral of the world. At the entrance, a painted gate proclaims: “You are entering a rebel territory. Here the people command and the government obeys.” There are several Caracoles—Oventic, La Realidad, La Garrucha, Morelia, Roberto Barrios—each representing a Zapatista region and autonomous community. These are living places: schools, clinics, women’s houses, councils of good government. Nothing here is decorative—everything is necessary. The Zapatistas are not legends from the past. They are here, alive, discreet, tenacious, and their struggle is not limited to the 1994 uprising. They build, day by day, another world on the margins of ours—a world without bosses, without parties, without electoral promises. A world woven from collectivity, dignity, and horizontal organisation.

Todas las fotos fueron tomadas por mí y se publican con el consentimiento de las personas fotografiadas. Realizadas con una Nikon D3400 y un objetivo AF-P 70–300 mm.

Soy frances 🇨🇵️ aficionado de cultura de sur america 🇪🇸 . Eso es un intento de escribir una historia en Español que aprendí viajando. La version Inglesa 🇬🇧 es una traducion de Google translate. English version is a Google translation.

Gracias por su lectura ✨ → Encuentrame en Hive : @terresco → Todas mis historias (en Frances) : https://safary.eu/recits → Mis fotos de viaje : https://safary.eu