What a visit we had to view the Romanesque burial mounds in Cambridgeshire, England.

Tucked away in the sleepy village of Bartlow, where Cambridgeshire nudges up against Essex, there’s a place that feels like it’s holding its breath, waiting for someone to notice its secrets.

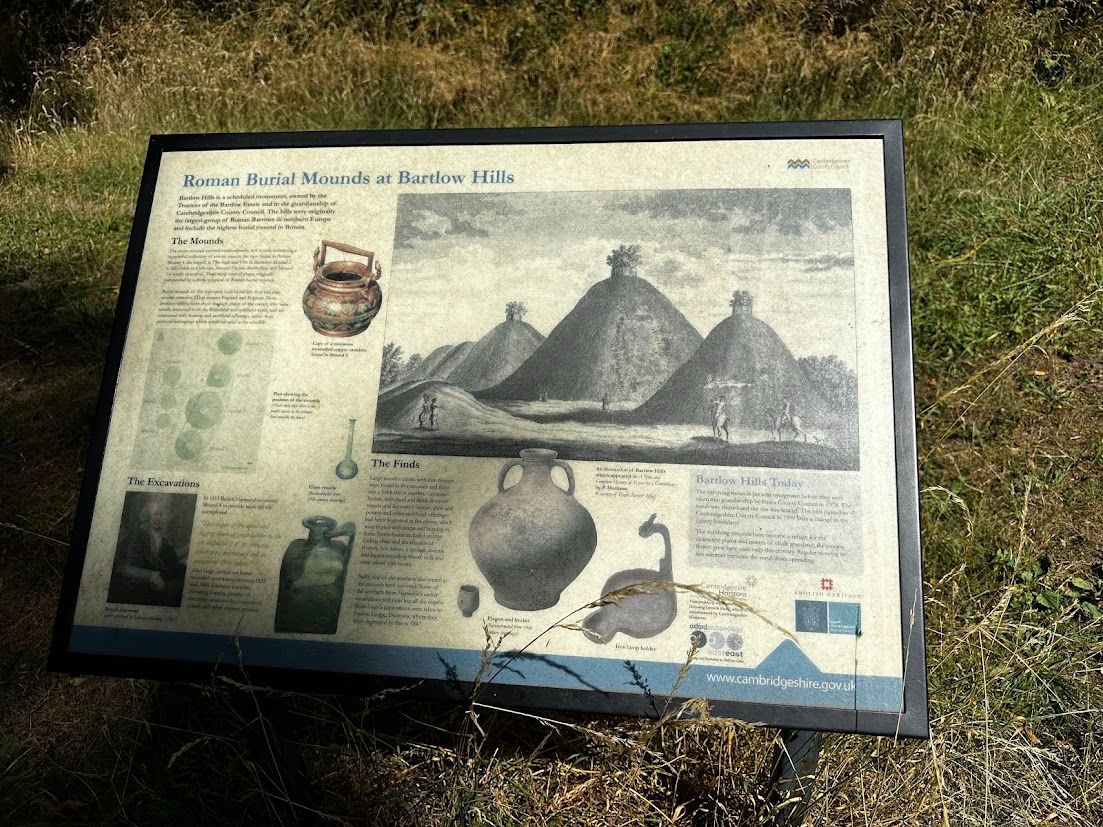

The Bartlow Hills, a cluster of Roman burial mounds from the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, rise from the earth like silent sentinels, their chalk and soil slopes whispering stories of wealth, ritual, and a world long gone.

I stumbled across them almost by accident, following a winding footpath past the Three Hills pub, and found myself standing before something both grand and forgotten, a hidden gem in Britain’s historical tapestry.

There were once seven of these mounds, or so the locals say, but only four still stand proud, their conical shapes cutting a striking silhouette against the sky.

The biggest, Mound IV, looms at 15 meters high, its base sprawling wide enough to make you feel small as you crane your neck to take it in.

It’s the tallest burial mound in Britain, they tell me, and one of the largest north of the Alps.

The other three are smaller, about 7 meters high, but no less imposing, clustered together in a neat row like a family keeping watch over the fields.

The other three mounds? Two were flattened by farmers long ago, their outlines barely traceable now, and one was obliterated when a railway sliced through the land in 1862.

It’s a shame, really, to think of what was lost to progress.

These hills aren’t just piles of earth.

They’re deliberate, crafted with care, their steep sides and surrounding ditches giving them an almost sacred air, like they were meant to stand apart from the everyday world.

Walking among them, you can’t help but feel they were built to impress, to make people stop and wonder who was important enough to be buried here.

The Romans brought their flair for grandeur, but there’s something older in the way these mounds rise, something that feels tied to the ancient British habit of marking the dead with earth and stone.

It’s as if the local elite, whoever they were, took Roman ways and wove them into their own traditions, creating something uniquely theirs.

Back in the 1800s, curious minds dug into these hills, unearthing treasures that painted a picture of lives steeped in wealth and ritual.

They found walled graves, cremated remains tucked into glass jars, and wooden chests bound with iron, stuffed with riches.

There were bronze and enamel vessels, some so finely crafted they must have come from far-off places like the Rhineland or northern Gaul.

One mound held a folding iron chair, a rare thing that screams status, and another had lamps with burned wicks, their faint traces of fat suggesting they were left glowing as the tomb was sealed.

I can almost see it: a flickering light left to guide the dead into whatever comes next.

They even found traces of flowers, incense, and wickerwork, preserved in the dry chalk like a moment frozen in time.

It’s the kind of thing that makes you pause, imagining the hands that placed those offerings, the care they took.

Sadly, a fire at Easton Lodge in 1847 destroyed many of the finds, a gut-punch for anyone who cares about history.

What survived—a tiny enameled copper cauldron, a few other bits and pieces—sits in museums in Saffron Walden, Colchester, and Cambridgeshire.

Those artefacts tell us these weren’t just graves; they were statements.

The goods weren’t personal trinkets but feasting gear, sacrificial offerings, the kind of thing you’d see in Roman burials across eastern England and Belgium.

Whoever was buried here wasn’t just rich—they were connected, part of a network stretching across the Empire.

The hills sit in a landscape that feels alive with the past.

Just north of the mounds, archaeologists found a Roman villa, occupied until the late 4th century.

It’s easy to picture it: a sprawling estate, maybe home to the family who built these tombs, their lives tied to the land and the wealth it brought.

The River Granta flows nearby, and the border between Cambridgeshire and Essex feels like a line drawn between worlds, a place where Roman influence met local roots.

Standing there, you can almost feel the hum of that ancient life, the bustle of a household that could afford to build monuments like these.

Yet for all their grandeur, the Bartlow Hills are easy to miss.

No big signs point the way, just a quiet path through the woods.

The mounds are hidden by trees, invisible from the road, which only adds to their mystique.

You can climb the biggest one, if you dare trust the rickety wooden stairs—locals warn they’re falling apart, and I wasn’t brave enough to test them.

From the top, I’m told, you get a view of the rolling countryside, a rare hilly patch in flat Cambridgeshire.

It’s a place that feels both remote and intimate, like it’s been waiting for you to find it.

The site’s not perfect, mind you.

It’s a scheduled monument, looked after by the county council, but the upkeep’s spotty.

Brambles and weeds creep over the paths, and those stairs need fixing.

Still, there’s a kind of magic in the neglect.

The chalk mounds, useless for farming, have become a haven for wildflowers and insects, a little pocket of nature thriving where history sleeps.

It’s a reminder that time doesn’t just preserve—it reshapes.

For years, people got the story wrong.

Some thought these hills marked the Battle of Assandun in 1016, tied to King Cnut, but the excavations put that to rest.

They’re Roman, through and through.

Nearby, St. Mary’s Church with its rare round tower—built in the 11th or 12th century—adds another layer to the place, though it, too, was once mislinked to Cnut.

Standing between the church and the mounds, you feel the weight of centuries, Roman and Saxon and medieval, all tangled together.

There’s something about the Bartlow Hills that sparks the imagination.

Some say their seven peaks echo the seven hills of Rome or even the Pleiades in the sky, though that’s probably just fancy.

Others talk of ley lines, those old mystic threads crisscrossing the land, but I’m not one for such tales.

What I do know is that these mounds were meant to be seen, to tower over the fields and say something about the people beneath them.

They’re not just graves—they’re a claim to eternity.

Visiting Bartlow Hills feels like stumbling into a secret.

They’re not on every tourist map, and maybe that’s for the best.

There’s a quiet power in their obscurity, in the way they’ve stood for nearly two millennia, half-forgotten but unyielding.

They remind you that even the grandest lives fade, but the earth holds tight to their memory.

If you ever find yourself in Bartlow, take the path past the pub, step into the shade of the trees, and let the hills tell you their story.

It’s one worth hearing.

The Bartlow Hills, rising like ancient guardians in a quiet Cambridgeshire corner, hold secrets of Roman wealth and ritual.

Their chalk mounds, once seven, now four, whisper of elite lives and distant trade. Hidden by woods, they’re a forgotten marvel, their story etched in earth, waiting for curious hearts to uncover.

Thank you for reading. I hope you enjoyed this summary of the Bartlow Hills Burial Mounds and the pictures of our field trip.